I don’t know if they hand out awards for the most optimistic investor relations team, but the gang at Alexandria Real Estate Equities just opened 2026 with a banger that will surely make them the top candidate. Yes, it’s been a rough three years for the nation’s largest owner of buildings dedicated to the pharmaceutical and biotechnology industries. The share price has fallen by 75% since the pandemic and they just slashed the dividend. But despair not ye of little faith. Just think about all of those diseases out there looking for a cure!

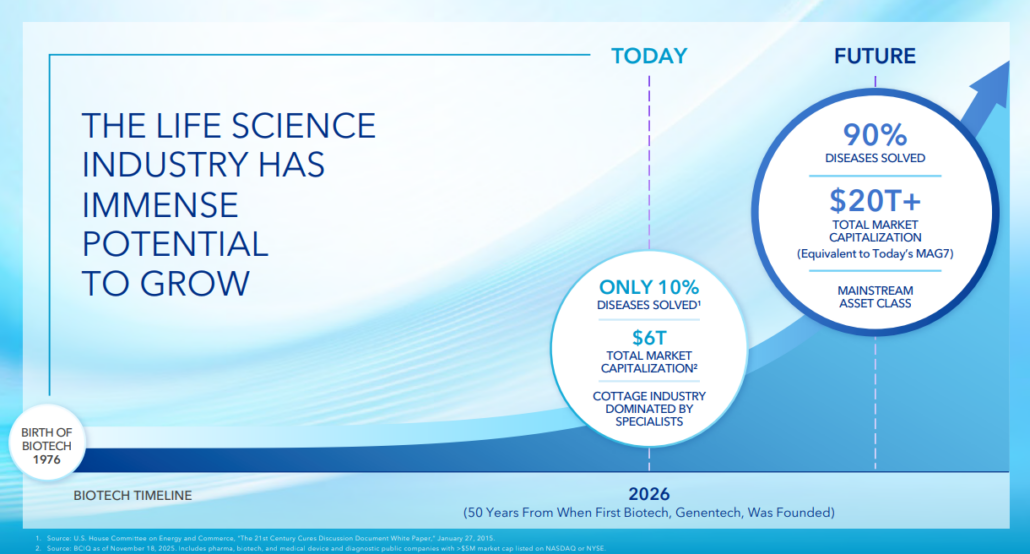

The Alexandria slide deck announces our glorious pharmaceutical future by declaring that only 10% of earthly diseases have been “solved”. That leaves 90% of the rest of the diseases left to cure. Talk about upside! The current market capitalization of the biotechnology industry is estimated by Alexandria to be $6 trillion. Extrapolating this figure for the next 80%, well, that’s another $14 trillion of potential market capitalization lying just beyond the rainbow. The god-like powers of capitalism will save humanity.

Alexandria’s team must have considered the irony of this future. After all, once 100% of the remaining diseases are “solved”, the market capitalization of the biotech industry should be closer to zero than $20 trillion. Realizing the potentially adverse effect of curing all diseases, they left open the possibility that 10% of the remaining diseases are beyond the grasp of even the most miraculous biotechnical engineering.

Because, when you get right down to it, solving all diseases isn’t great for business. No, what we really need is a sort of Munchausen-by-proxy economy. By all means, come up with ways to treat the ills of mankind which improve comfort and extend lifetimes. But cure? Now, hold on there, that’s a lot of jobs we’re talking about. Healthcare is now more than 16% of our nation’s GDP. You know what might work even better? What if we re-introduced diseases that were already “solved”? Take measles, for instance. Who knows? A resurgence of leprosy might be just what we need to avoid the next recession.

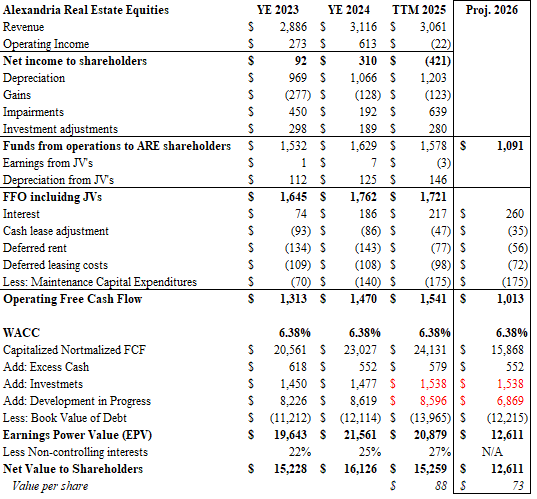

Ok, enough joking around. In fairness to Alexandria, much of the presentation describes the precarious state of the life sciences real estate market and the challenges facing the company. The real question before the house is whether shares in Alexandria Real Estate Equities (ARE) offer investors compelling value. The nation’s largest owner of real estate dedicated to scientific research claims that the net value of its assets is far higher than the current $54 share price. Alexandria’s investor presentation asserts that the true value is closer to $94. In my estimation, the shares are worth about $73. However, I won’t be buying stock any time soon. Much of this premium is based upon the book value of an uncertain development pipleine and the value of its speculative securities investment portfolio.

In this article, we’ll take a brief overview of the latest investor presentation, and I will guide you through some numbers that compose my valuation.

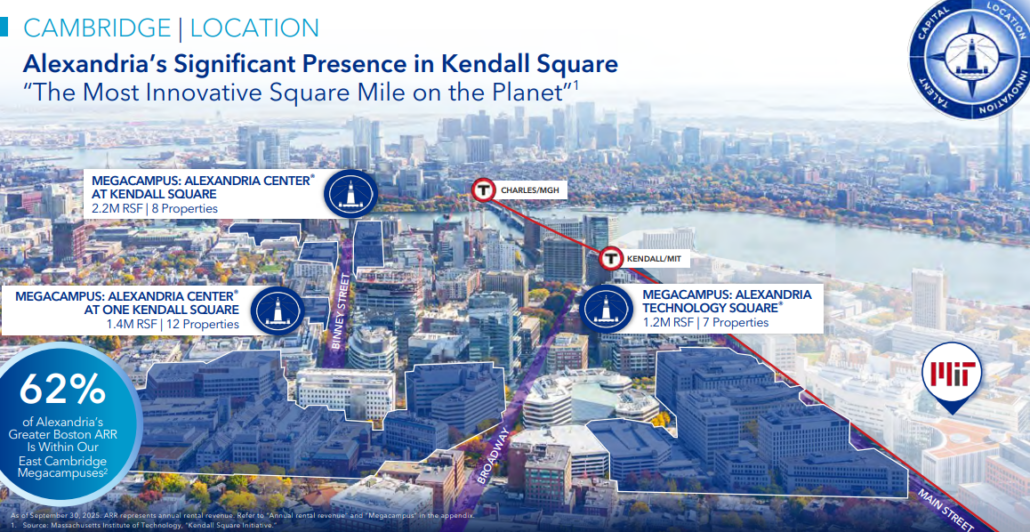

Alexandria has shaped its nationwide real estate portfolio into 26 dynamic innovation campuses. Primary markets include Boston, San Diego, San Francisco, Seattle, and DC. The company boasts a tenant roster of 700 companies in 27.1 million rentable square feet. Tenant retention has been over 80% over the past five years. Scientific innovation thrives when disparate groups of creative thinkers interact on a frequent basis. Despite the rise of remote work, it seems likely that medical technology will continue to emerge from the laboratories and offices of pharmaceutical companies, research universities, and medical device manufacturers.

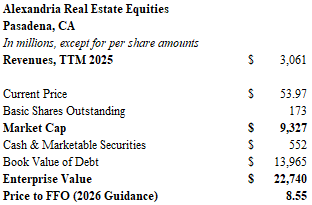

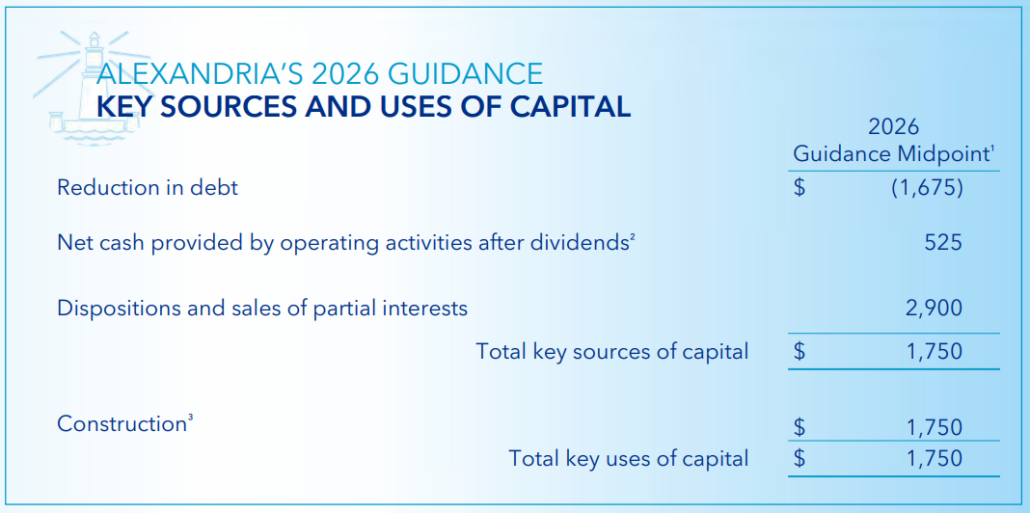

Alexandria trades with a market capitalization of $9.3 billion and the current price allows for a 5.3% dividend yield on the reduced payout. The share price is roughly 8.6 times management’s guide for 2026 funds from operations (FFO). The undepreciated book value of real estate on its ledger amounts to $29.3 billion, with another $8.6 billion of construction in progress at the end of the 3rd quarter of 2025. The company has approximately $13.9 billion of debt and lease obligations. To improve the balance sheet, Alexandria intends to dispose $2.9 billion of “non-core” real estate assets and joint venture interests in 2026. ARE forecasts 2026 operating cash flow (after dividends) of $525 million. The resulting $3.4 billion cash pile will be split: $1.7 billion for debt reduction and $1.7 billion for the completion of construction projects.

Alexandria is rated BBB+ by Standard and Poor’s but has been placed on a negative credit watch. Still, the company does benefit from a low cost of financing and a long runway for debt maturities. The weighted average interest rate for ARE’s debt is 3.97% and the weighted average maturity is 11.7 years. Unfortunately, recently issued debt came with a 5.6% coupon.

The reasons for worrying about Alexandria’s future are easy to find. Winter has arrived for the medical technology industry. Demand for life science space has fallen 60% since the pandemic. To make matters worse, the most recent Senate budget presents a 40% decline in spending for the National Institutes of Health (NIH) to $48.7 billion. It is estimated that 1,500 jobs will be eliminated. Meanwhile, only about $9 billion of venture capital funding is anticipated for the medical technology industry in 2026. This represents a substantial reduction from 2021 when $41 billion was raised. Pharmaceutical company spending on research and development peaked in 2023 at $317 billion and has fallen the past two years.

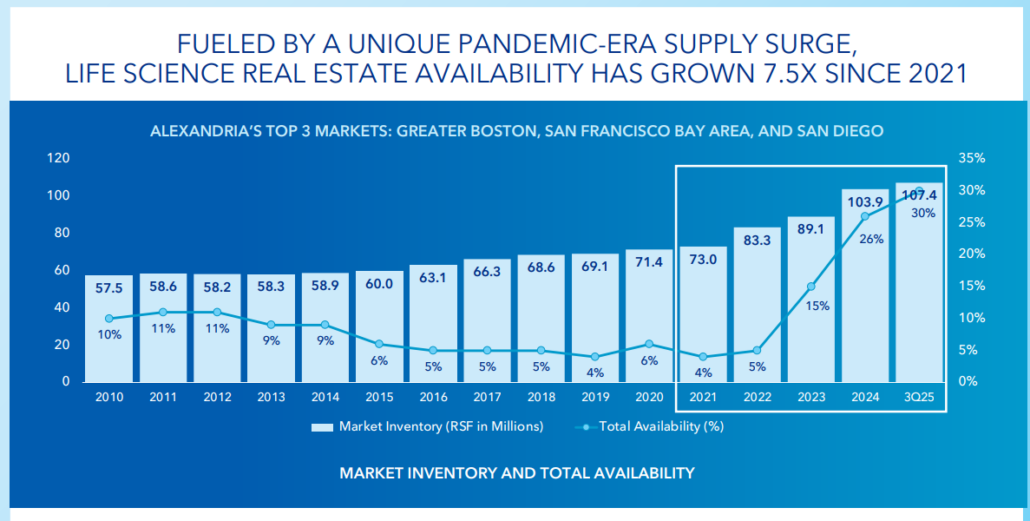

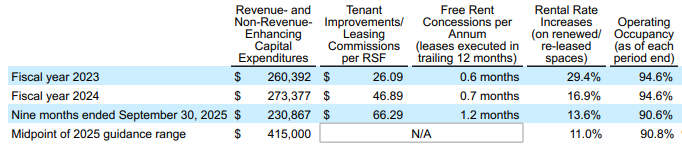

Market occupancy levels have dropped precipitously. Over 30% of space is available in the company’s top three markets of Greater Boston, the San Francisco Bay Area, and San Diego. Occupancy levels at Alexandria’s buildings reflect the industry decline. They fell dramatically from 94.6% at the end of 2024 to 90.6% at the end of the 3rd quarter of 2025. Any time real estate owners see an occupancy level with an 8 in front of it, beads of sweat start to appear. Occupancy at Alexandria is forecast to drop to as low as 87.7% by the end of 2026.

More problems could lie ahead. Alexandria has a plan for 2026, but what about the completion of projects in 2027 and 2028? Future capital raises to finish buildings in progress may be needed, and they will certainly dilute current shareholders. At the end of the 3rd quarter of 2025, Alexandria projected that 4.2 million rentable square feet will be placed into service between the end of 2025 and 2028. 43% of the new space is under lease or in negotiation. This new space is expected to generate more than $390 million of NOI. But that assumes another 2 million square feet has yet to be absorbed in what promises to be a soft market. It could take many years to backfill the overall 30% market availability in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Finally, the entire cost structure of newer assets may face a pricing reset. Capital improvements amounted to $260 million in 2023, but they were expected to rise to $415 million by the end of last year. On a per square foot basis, TI’s and commissions rose from $26 to $66 over three years. Free rent to secure new leases has doubled during the timeframe. Even the strongest pharmaceutical companies will balk at the rental rates on offer and demand substantial concessions.

Alexandria forecasts that 2026 FFO will fall from approximately $9 per share in 2025 to $6.40 per share in 2026. While dispositions account for a large portion of the reduction, rents on lease renewals are forecast to fall by as much as 12%. Same-store net operating income will drop by as much as 9% in 2026.

Valuation

My valuation method is very simple. I took $1.1 billion of projected funds from operations for 2026, added back the forecast interest expense of $260 million, subtracted $175 million for maintenance capital expenditures, and subtracted cash lease adjustments. The cash lease adjustments are identical to the numbers for 2025, but they have been reduced by 27% to estimate the portion attributable to joint ventures. The resulting free cash flow from operations for 2026 is estimated to be approximately $1 billion. This sum was divided by a capitalization rate of 6.38% to arrive at $15.9 billion of value.

Next, I added $552 million of cash on hand, the securities investment portfolio of $1.5 billion and the book value of construction in progress of $6.9 billion. Construction in progress was calculated by subtracting $1.75 billion from the September 2025 balance of $8.6 billion. Finally, after accounting for management’s guidance of $1.75 billion of debt reduction, the 2026 debt level of $12.2 billion was subtracted. The net value is $12.6 billion, or approximately $73 per share.

The table shows the change in computed net asset value over the past three years. In 2023 through 2025, I “grossed up” funds from operations to include joint venture partnerships before capitalizing the cash flow. An adjustment was made at the bottom using a percentage of book value attributable to noncontrolling interests. My calculation for 2025 indicates a net asset value of $88 per share, showing that a substantial decline in the stock was justified.

My capitalization rate is based on a weighted cost of capital where the market value of net debt accounts for 56% of the measure. At a BBB+ rating, the cost of debt was attributed as 5.1%. This is a forgiving number considering the recent placements at higher rates. Equity, the remaining 44% of the weight, was awarded a simple 8% rate. I don’t have a sophisticated explanation for the use of 8%, but it generally “feels right”.

You may think my cap rate is too high considering the gold-plated roster of tenants like Lilly and Merck and the proximity to the best universities in the world. Alexandria touts its asset values utilizing capitalization around 6% and below. Yet, the company has sold assets at cap rates above 8.5%. The building sales may may not represent “core assets,” but such a wide discrepancy can’t persist as long as interest rates remain elevated.

Although the calculation offers the appearance of upside, far too much weight is placed on the book value of construction in progress and the value of the company’s securities. Alexandria often took equity stakes in their tenants in lieu of rent. Given the uncertainty around new drug approvals, much of the securities portfolio could become impaired. Meanwhile the full lease absorption of $6.8 billion of construction in progress is far from certain. In the early years following completion, hefty concessions will be required to attract tenants. One can easily see that a 30% impairment of the development pipeline would eliminate the premium calculated in my valuation. The market may well be ascribing such a discount already.

Alexandria Real Estate Equities offers an intriguing way to invest in the future of the pharmaceutical industry. Medical innovations will continue to emerge, of course, and they may occur more frequently than not at one of Alexandria’s campuses. The company has a best-in-class real estate portfolio and has proven to be a skilled operator and attractor of premier tenants. But nobody is immune to the laws of supply and demand. There is simply too much laboratory space on the market, and the engines of demand are looking fairly dormant. When the government is no longer a key partner in the development of new drugs, your runway looks a lot cloudier. Is there upside? Probably so. But, I think there are better places to put your money in the meantime.

If you are attracted to Alexandria’s robust dividend yield, I would look elsewhere. Some of the pipeline master limited partnerships (MLPs) are more appealing. Western Midstream (WES) and Hess Midstream (HESM) yield about 9%, and the demand for natural gas seems much more reliable as power generation capacity continues to grow. Along those same lines, some of the big miners stand to benefit from the copper and minerals boom. BHP yields 3.5%, Rio Tinto is on 4.6%, and the much riskier Vale yields more than 8%. I would add that the large mining companies provide the added benefit of diversifying away from a deflating dollar.

We’ll leave it there for now. Until next time.

DISCLAIMER

The information provided in this article is based on the opinions of the author after reviewing publicly available press reports and SEC filings. The author makes no representations or warranties as to accuracy of the content provided. This is not investment advice. You should perform your own due diligence before making any investments.

Evolution AB is a Swedish gaming company that trades on the Stockholm bourse. About 622 krona will buy you a share, and that price gives Evolution a market capitalization of about €11.6 billion. Evolution develops and operates games that “sit behind” many well-known gambling sites. They continually find new dopamine-enhancing ways to keep punters glued to their devices, losing money to the house in rapid-fire succession. Most games seem to target the unsophisticated bettor. “Coin Flip”, “Cash Hunt” and “Crazy Time” are just a few of the offerings. More interestingly, they also offer traditional casino games like poker and roulette by hosting players online with live studios situated around the world.

I passed on Evolution earlier this year, but I decided to take another look at after reading a recent Bloomberg article about the investment activities of Kenneth Dart who is taking large positions in the gambling industry through Evolution and Flutter. Flutter owns FanDuel, Paddy Power Betfair, SportsBet, and Poker Stars. Or, if you prefer, just about half of the kit sponsors for English football. In a clear indication of modern society’s moral compunctions, England has banned alcohol sponsors on their team jerseys for well over a decade, but they have no problem with gambling companies emblazoned across players’ chests.

Kenneth Dart is the billionaire heir to the plastic container fortune. When he’s not crafting ways to avoid paying taxes, he is busy investing in “sin stocks”. He had a phenomenal run of success with tobacco firms recently. The thesis seems to be similar for his investments in online gambling: it’s widespread, increasingly legal, and totally addictive.

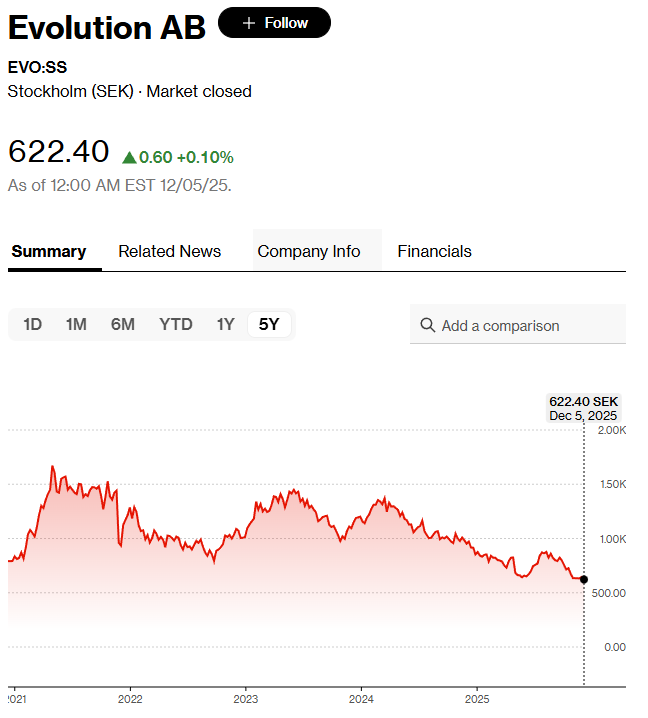

Evolution trades with a trailing PE slightly above 10, and an EV/EBITDA multiple of 7.4x. After a brief summer rally, shares hover near 52-week lows. Evolution is 62% below its all-time Covid high, and down 26% since the beginning of 2025. Notably, Dart’s largest investment in the company occurred before the most recent drawdown.

Revenues at Evolution grew at a compound rate of over 25% annually between 2021 and 2024. Unfortunately, the combination of high growth and diverse worldwide internet hosting services attracted the sort of nefarious folks who’ve always lurked in the gambling shadows. Hackers in Asia inflicted widespread outages and security breaches upon Evolution last year. Revenue has plateaued over the past 12 months. The stock price reflects the lost momentum.

Evolution’s leaders assure shareholders that the security problems have been solved and the company is ready to grow once again. I have found CEO Martin Carlesund’s messages to shareholders to be refreshingly blunt in their assessment of the company’s shortcomings. Accountability seems to be part of the vernacular at Evolution. It is a sharp contrast with another downtrodden company I have been researching: DentsplySirona (XRAY).

One might think that straight talk would be needed at a company which has lost 83% of its market capitalization, but that is not the case! DentsplySirona is not only a really horrible name (did they leave out letters to remind us of missing teeth?), the annual report is a load of jargon-filled blather that leaves one wondering if the company is a dental supply company or a multi-level marketing scheme. It certainly makes no apologies for an atrocious capital allocation track record and probably isn’t worth my time putting pen to paper. But we’ll talk about that later. Moving on.

Evolution is asset-light, has an operating margin of 60%, and posts returns on capital in excess of 30%. The company pays a well-covered dividend, and the yield is nearly 5%. If they can right the ship and return to growth, the upside is compelling.

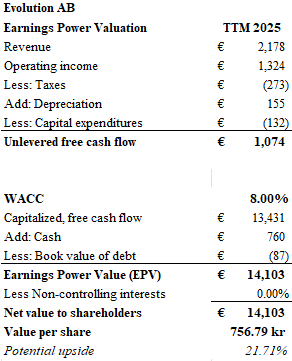

My preferred valuation model is the basic Earnings Power Value (EPV) method advocated by Bruce Greenwald and his peers at Columbia. In the tradition of Ben Graham, normalized unlevered free cash flow is simply capitalized by the weighted average cost of capital (WACC) to arrive at a value for the firm. Subsequently, net debt is subtracted to arrive at a value of the equity. In the case of Evolution, unlevered free cash flow over the trailing twelve-month period was just slightly less than €1.1 billion. Using a WACC of 8% to capitalize this amount results in a value of €14.1 billion once one accounts for the net cash position on the balance sheet. On this basis, Evolution trades at a 22% discount to its market price.

As always, I struggle with the proper cost of equity to employ in my valuation. I don’t use betas and assigning a cost to the equity is easier if you can assume a spread above the firm’s cost of debt. Since Evolution is unlevered, the 8% rate has a swaggy feel to it. Should it be lower? This is not a European company. Revenues are international, so pricing off the 10-year Bund doesn’t work. Arguably any company that is vulnerable to hacking and relies on programming talent anywhere from Tbilisi to Taipei should be valued accordingly. Using a WACC of 10% puts the value closer to par.

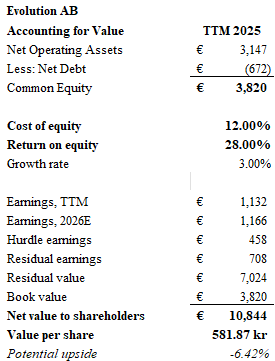

The other valuation model I’ve been using lately is the “accounting for value” method from the book Financial Statement Analysis for Value Investing. Stephen Penman and Peter Pope are CPAs by training and they take book value as the foundation. Next, they add the value of future growth. The authors rightly state that a company’s future growth is only valuable to the extent that the return on equity exceeds the cost of equity. They take this “surplus” return and discount it at the cost of equity less the assumed rate of growth. The higher the growth, the lower the denominator, the larger the value of future earnings. The model can be especially useful if one works backward: it tells you what level of growth is necessary to justify the current price.

If one assumes a cost of equity of 12% for Evolution, and a return on equity of 28% consistent with recent performance, the future “surplus” earnings calculate to €708 million assuming a growth rate of 3%. This results in a value 581 krona per share, once again, roughly in line with the current price.

But what happens if growth resumes at a rate higher than 3%? A 5% future growth rate results in a share value of $705 krona, or 13.4% upside. A 6% growth rate translates into $798 krona, or 28% upside.

Is the market for online gambling going to grow faster than worldwide GDP over the coming decade? It seems plausible. There is an insatiable willingness to gamble on literally everything, and the ubiquitous access to gaming through a phone makes it easily accessible. Might there be a backlash? Names like “Coin Flip” and “Cash Grab” imply a simplicity that can be very appealing to children, so it wouldn’t be surprising if there is a worldwide recognition that the proliferation of gaming is leading to problems with youth delinquency. But sadly, I think that regulatory horse has left the barn.

Evolution has created a lot of valuable intellectual property, its games are entrenched in the gambling site ecosystem, and the investment in live studios provides punters with the authentic feel of a casino. The lack of debt, high dividend yield and substantial margins seem to present downside protection. I believe the returns on equity are significant enough that the firm can reinvest its ample cashflow into growth that will exceed 5% over the next decade, so I consider the shares of Evolution to be priced 10-25% below the intrinsic value of the business. Fortis fortuna adiuvat.

Until next time.

DISCLAIMER

The information provided in this article is based on the opinions of the author after reviewing publicly available press reports and SEC filings. The author makes no representations or warranties as to accuracy of the content provided. This is not investment advice. You should perform your own due diligence before making any investments.

Unlike most Hollywood scripts, media deals rarely live happily ever after. Disney is still healing from the acquisition of 20th Century Fox for $71 billion in 2019, which drew the ire of activist investor Nelson Peltz. The AOL-Time Warner merger of 2000 proved to be a fiasco. Even now, the heavy debt load carried by Warner Brothers Discovery is part of that legacy.

It came as quite a surprise to see Warner Brothers shares surge more than 33% last week as news spread of a pending bid from David Ellison’s Paramount Skydance. It has only been five weeks since the son of Larry Ellison muscled his way into ownership of Paramount for $8 billion. A deal for Warner Brothers would be larger by several orders of magnitude – in excess of $71 billion, including WBD’s onerous $35 billion of debt.

Contrast the swashbuckling exploits of Ellison with Brian Roberts, the second generation CEO of Comcast. Roberts transformed the cable company into a modern media giant by launching attacks during moments of industry distress. Comcast acquired AT&T’s broadband business in 2002 in the wake of the dot-com bubble, and preyed upon the ailing General Electric to buy NBC Universal in 2011.

Comcast (CMCSA) stock presents an appealing investment opportunity. The share price has declined 46% since it peaked during the pandemic lockdown. Although the company faces growing competition from new fiber networks and fixed wireless providers, Comcast continues to increase revenues. In my estimation, Comcast trades at a 44% discount to the intrinsic value of its business.

Comcast, America’s largest broadband provider, generated over $124 billion in revenue over the past 12 months. The Philadelphia titan produced $12.5 billion in free cash flow in 2024.

The following article offers a brief discussion of Comcast followed by a simple valuation presentation. I employ the earnings power value model (EPV) favored by Columbia’s Bruce Greenwald in the tradition of Graham and Dodd.

Comcast shares currently trade with a PE ratio of 11 and an attractive EV/EBITDA multiple of 5.6. The free cash flow yield exceeds 10%. While the equity price languished, over $13.5 billion of cash was returned to shareholders in 2024: $4.8 billion in dividends were awarded, and $8.6 billion of stock was repurchased. The current dividend yield is nearly 4%.

Comcast recently announced that it will spin-off some lower-tier networks to shareholders later this year. The new company will be known as Versant and will hold legacy networks such as CNBC, E!, USA and the Golf Channel. Various digital assets like Rotten Tomatoes will also be included. Notably, NBC and the Peacock streaming service will remain with Comcast.

So why have Comcast shares performed so badly since 2021? Despite increasing revenues per user and a successful rollout of Xfinity mobile, Comcast has been losing customers in its legacy broadband and cable businesses. Although new lines of revenue are emerging, the content side of the business is much smaller. Unfortunately, it is also less profitable.

“Connectivity and platforms” accounted for 64% of Comcast’s $123.7 billion of 2024 revenue. These fixed-cost broadband and cable services offer tremendous operating leverage. EBITDA margins are 40%. Meanwhile the studio, network and theme park businesses have EBITDA margins of 20%. Reinvesting the cash from legacy broadband into media content is a fruitful exercise, but it can’t replicate near-monopoly profits the company once enjoyed.

Blockbuster movie releases like Jurassic World and Oppenheimer produce hundreds of millions in profits, not billions. New theme parks in Beijing and Japan are hitting their stride, but European expansion plans won’t move the needle much. The Peacock streaming service has yet to turn a profit, and Comcast recently bolstered the content of the streamer with an expensive NBA deal – a league suffering from declining viewership.

One can’t deny that a Paramount-Warner merger would represent a threat to Comcast. The venture could drive higher prices for content carried by Xfinity’s cable network, and a combination of two of the largest film studios might harness more resources into production. Ellison has already lured Jeff Shell, CEO of NBC Universal to Paramount.

The Roberts family controls Comcast through a solid lock on the company’s B shares. The lack of voting power in the A shares may be a further cause for a market discount.

Substantial growth will likely come from another transformative acquisition by Brian Roberts. The question is whether or not a bargain can be had. Will Comcast enter the fray and make a bid for Warner Brothers? It seems unlikely that Roberts would be interested in a bidding war.

And yet, the $71 billion enterprise value of WBD is roughly seven times EBITDA. Not cheap, but not unreasonable either. This multiple is slightly deceptive. Film and television content rights cost Warner Brothers more than $12 billion per year in working capital. Still, cash provided by operations was $5.4 billion in 2024 on $39.3 billion in revenues. All of the surplus funds went towards debt reduction.

William Cohan, the noted author and former Wall Street banker, has followed the Comcast story closely. Writes Cohan, “Though he was the son of Comcast architect Ralph Roberts, the entrepreneur who built the cable systems empire that mushroomed into the media behemoth, Brian rejected any sort of born-on-third base implications. He was immensely driven, aggressive, ambitious, and carnivorous.” While it may be nothing more than an anecdote, the word carnivorous is not usually associated with a patrician Philadelphia gentleman content with counting his stack of money. Growth is in his DNA. So is discipline.

Let’s turn to the value of the business.

The earnings power valuation (EPV) model results in an estimated price of $48 for Comcast’s shares. This represents potential upside of over 43% compared to its current $33.50 trading level.

Comcast is rated A- by Standard & Poor’s. The company benefits from a well-managed debt profile amounting to $101.5 billion at the end of the June 2025 quarter. The weighted average interest rate on Comcast debt is 3.8% and the weighted average maturity is 15 years. Given that rates for similar quality obligations would be approximately 4.8% today, Comcast debt carries a market discount which puts it in the range of $98 billion.

The weighted average cost of capital for Comcast was calculated at 6.87%. This represents the aforementioned 4.8% debt cost (or about 3.7% after taxes) accounting for 41.5% of the company’s capital, and an equity cost imputed at 9.1%. The cost of equity is precisely imprecise. I don’t use beta, and I also don’t select an arbitrary “hurdle” rate. My cost of equity is a sum of the 10-Year Treasury Note at 4.03% plus a 0.75% debt spread for A- paper. Finally, I add an equity risk premium of 4.33%. The result is an equity cost of 9.1%, which seems reasonable given Comcast’s stable cash flow.

Operating income over the trailing twelve-month period amounted to $22.5 billion. Subtracting taxes of $5 billion, adding depreciation of $15.7 billion and subtracting capital expenditures of $14.6 billion, leads to unlevered free cash flow of $18.6 billion. Divide this number by the 6.87% WACC, and you have a capitalized gross value of $271.1 billion. Subtracting net debt of approximately $89 billion leads to a value for shareholders of $181.2 billion, or roughly $48 per share.

Patience will ultimately prove to be profitable for Comcast investors. While one waits for Roberts and his team to take advantage of turmoil in the Disney, Paramount and Warner Brothers universe, share repurchases and a hearty dividend make the waiting worthwhile.

Until next time.

DISCLAIMER

The information provided in this article is based on the opinions of the author after reviewing publicly available press reports and SEC filings. The author makes no representations or warranties as to accuracy of the content provided. This is not investment advice. You should perform your own due diligence before making any investments.