RIP Bob Uecker.

Unless you’re shopping for vacant office buildings in ghostly business parks or depleted central business districts, there aren’t many bargains in commercial real estate. Investment cap rates defy logic. Plentiful sources of capital chase yields that are often below the cost of debt. This “negative leverage” conundrum only makes sense if we have major rent inflation. While this may well turn out to be true, inflation isn’t a one-way street. It will be difficult for rents to outpace operating expenses. Insurance and labor costs march relentlessly upwards, and I don’t expect struggling city governments to offer any property tax relief. But when your debt costs are fixed, inflation is usually your friend.

So are we witnessing a rational investment decision based on inflation outrunning the cost of debt, or are investors simply justfying a need to deploy capital? I suspect its mostly the latter. Asset prices across all sectors are at peak metrics. The casino is open. ETFs outnumber stocks, cryptocurrency treasury companies trade for double their underlying “assets”, and credit markets are priced to perfection. NVDIA dropped 3.4% on Friday. While this decline is eye-catching, the fact that it amounts to $143 billion – a dollar figure on par with the entire market capitalization of companies like Progressive Insurance and Lowe’s – should make one pause.

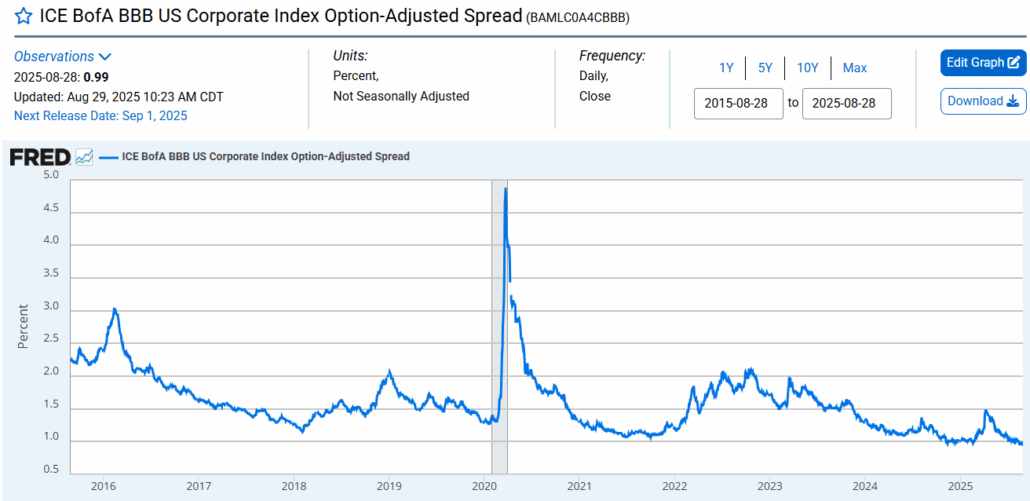

Nothing causes whiplash more than a painful case of mean reversion. Spreads have rarely been tighter. BBB spreads, a decent proxy for real estate cap rates, are below 1%. Meanwhile, new apartment deliveries are at generational highs. Many “hot” markets like Austin and Denver, now face an apartment glut. That rent inflation you were hoping for? It may take a while.

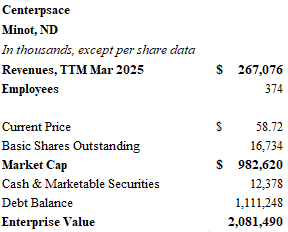

Given this backdrop, finding bargains among publicly traded apartment real estate investment trusts (REITs) is even more difficult. Let’s take the case of Centerspace, a Minot, North Dakota REIT with a market capitalization of $983 million. Centerspace (CSR) owns 13,353 units across the northern Midwest. Debt exceeds $1.1 billion. CSR has a strong presence in the Minneapolis area but has made an expansion push into Rocky Mountain markets. The 5.15% dividend yield looks appealing from a distance. Unfortunately, recent acquisitions at lofty prices will probably not improve the share price.

Investors in CSR have not had much joy over the past five years. Shares hover near $60, which is about where it stood prior to the pandemic. To management’s credit, CSR has begun to trade out of aging B-quality assets in favor of newly constructed apartment communities. The company also benefits from savvy borrowing moves during the COVID era. The cost of debt is safely below 4% and has a long maturity runway.

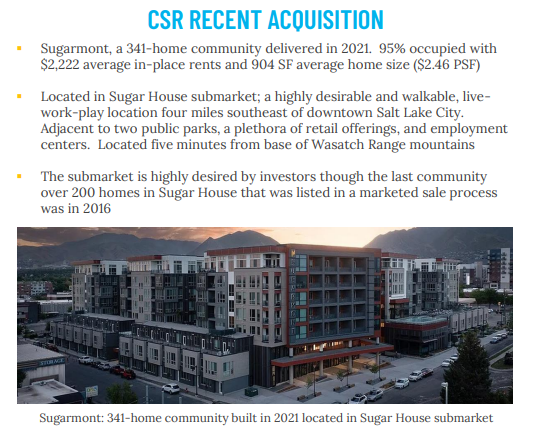

Efforts to modernize the portfolio seem to be having a positive impact on cash flow. Recent new acquisitions include a $149 million purchase of 341 units in Salt Lake City and a 420-unit property in Fort Collins, Colorado for $132.2 million.

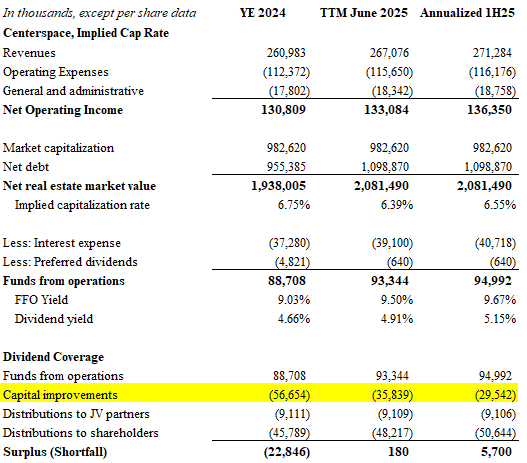

In 2024, Centerspace generated $88.7 million in funds from operations (FFO). After capital improvements of $56.7 million, distributions to JV partners and shareholder dividends, free cash flow was negative $22.8 million. The dividend appears to be on a more sustainable path today. Capital improvements are on trend to decrease to $29.5 million which will produce $5.7 million of positive cash flow.

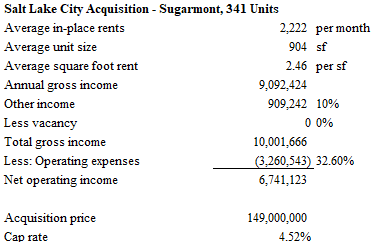

The acquisitions should enhance these results as they begin to filter through the income statement. However, it is hard to see how CSR meaningfully improves the languishing share price. The acquisition of Sugarmont, the 341-unit Salt Lake City property, wasn’t exactly a bargain. CSR paid $149 million for the vintage 2021 asset. I am not familiar with the SLC market, but it seems likely that the $437,000 per-unit price is not far from today’s inflated replacement costs. My estimation is that the purchase was made at a cap rate below 4.5%. Although CSR stands to benefit from the lower operating costs of a newer asset and a market with solid demographics, asset purchases at rates below the current dividend yield are unlikely to levitate share performance.

CSR informs us that they bought Sugarmont with average in-place rents of $2,222 per month. To be generous, I added 10% for other income. This would include items like pet fees, application fees, parking rent, and utility reimbursements. I was even more generous by assuming zero vacancy. Next, I took management at face value and assumed an NOI margin above 67%. The resulting net operating income (NOI) is $6.74 million. This figure translates into a capitalization rate of 4.52% on $149 million.

The reality is that even vertically integrated REITs have a very hard time running properties more efficiently than a 62% NOI margin. I don’t know the real estate tax and insurance landscape in Utah, but maintaining such a low level of operating expenses will be a challenge for Centerspace. As the company continues to shed aging properties for new assets, the cash flow performance should improve as capital improvement requirements decrease. However, acquisitions at lofty prices, and at cap rates below the dividend yield, will not improve investor returns. As loans begin to mature, even at a palatable pace, the debt must reset to rates that are 100-200 basis points above current levels. Centerspace is a pass for me.

I have made this point many times in these pages: a REIT that fails to deploy capital at advantageous rates cannot grow without issuing new shares. Real estate investment trusts are exempt from income taxes so long as they distribute 90% of taxable income. The inability to grow through the reinvestment of retained earnings turns a REIT into a dilution machine. Chose wisely.

Until next time.

DISCLAIMER

The information provided in this article is based on the opinions of the author after reviewing publicly available press reports and SEC filings. The author makes no representations or warranties as to accuracy of the content provided. This is not investment advice. You should perform your own due diligence before making any investments.

It was all going so well. Cigars and brandy around the hearth. Silk and cashmere. Fine Corinthian leather. The big industrial gas companies were having a jolly good time at the Oligopoly Club. Air Liquide, Linde, Taiyo Nippon Sanso and Air Products shared some laughs and enjoyed a few games of whist.

But across the street, a new eco-friendly club was opening. It was 2022, and the party was just starting. The DJ was laying down some insane beats. Air Products dreamily gazed through leaded glass at the crowd lining up behind the velvet ropes. It’s now or never…

Pulse quickening, cash in hand, Air Products suddenly stood below the green backlit sign. Club H2. One bouncer whispered to the other. Are they pointing at me? I’m in. This is happening.

Once inside, Air Products wasn’t so sure they made a good decision. Bottle service? Really? This seemed frivolous, but the hostess insisted. Three magnums of Cristal later, the room began to spin. Air Products saw an exit sign through the haze, but big guys in black t-shirts blocked the door. The next morning was, wait – it is the next morning.

I’m going to tell you about the misadventures of Air Products since 2022. The staid Allentown, Pennsylvania, company chased the illusive promises of a green future all the way to Saudi Arabia. Once the true costs and debt obligations became clear, shareholders revolted in early 2025. If you stick with me, I will also present two valuations for Air Products. Both methods indicate that the market price of the company’s shares is well above the intrinsic value of the business.

Industrial gases play a significant, if invisible, role in economic productivity. Hydrogen, oxygen, and their molecular cousins are essential for petroleum refining, fertilizer production, and the manufacture of metals and silicon wafers. Healthcare couldn’t function without oxygen and nitrogen. With such essential uses, industrial gas businesses can be very profitable.

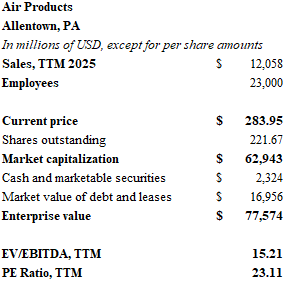

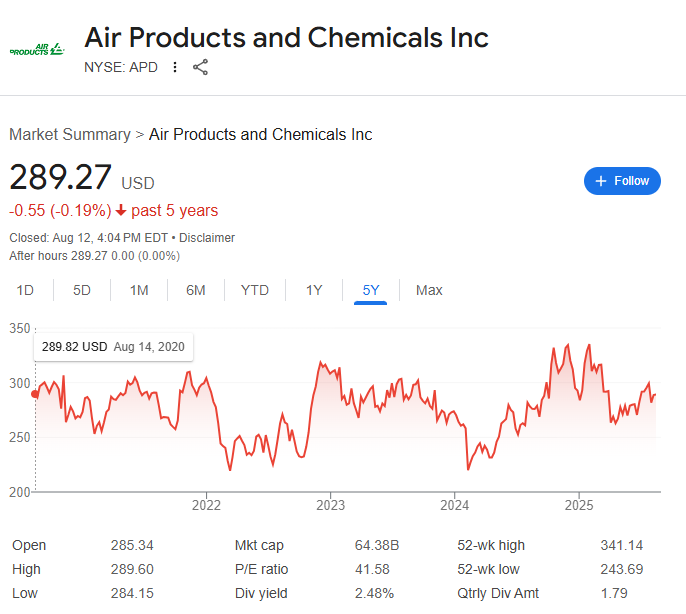

For many years, the world’s leading producer of industrial hydrogen was stable, boring, but steadily improving. Air Products was a stock you could recommend to your grandmother. APD generated over $12 billion in sales in fiscal year 2024. With a market capitalization of over $63 billion, Air Products grew earnings 7.5% per annum for a decade and dividends followed suit. Leverage was moderate. Capital investments flowed steadily from retained earnings. The company was responsible. It lived within its means. Returns on equity consistently posted in the mid-teens. Net margins hovered around 20%.

In 2022, Air Products was lured by the siren song of environmentally sustainable hydrogen production. Through a series of joint ventures, the company made substantial capital commitments. APD made an $8 billion promise to a blue hydrogen facility in Louisiana and a stunning $9 billion dollar commitment to a green hydrogen joint venture in Saudi Arabia. Three smaller sustainable hydrogen projects in the US accounted for a further $3.1 billion. Along the way, they divested their liquified natural gas business for $2 billion.

Air Products began to borrow. Big time. Long-term debt had hovered around $3 billion dollars for several years before surging to $7 billion after the pandemic, and then to over $13 billion today. Prior to 2022, capital expenditures were marching in line with depreciation at around $1 billion per annum. Recently, they have ballooned to over $4 billion per year. Free cash flow turned negative, and the dividend now seems precarious.

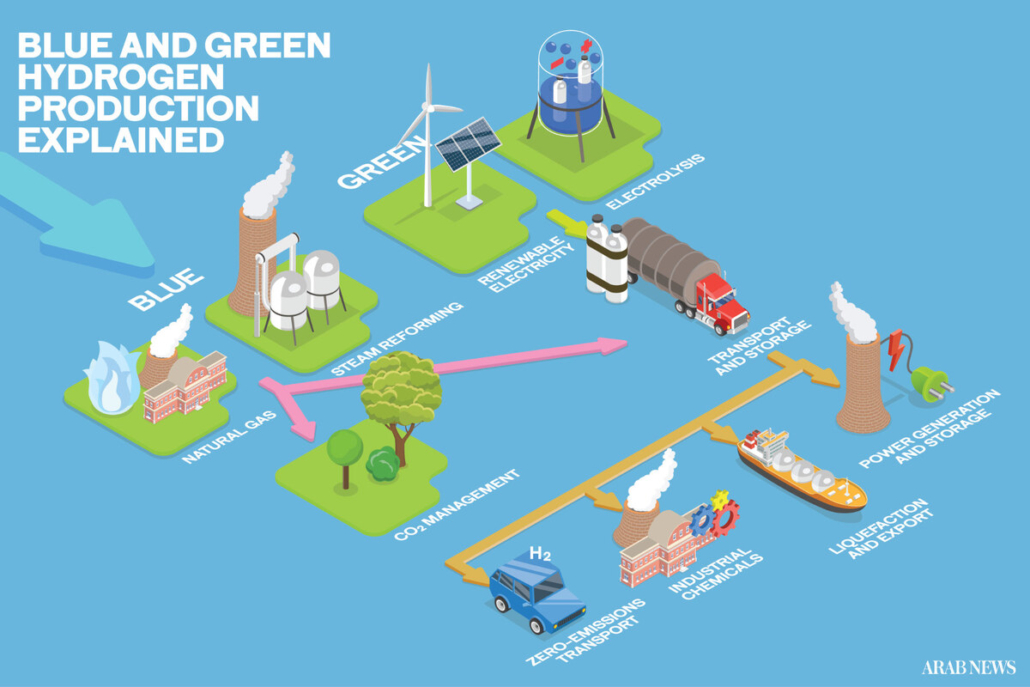

Most hydrogen is produced using a process known as steam methane reforming. High pressure steam separates hydrogen from methane (CH4), with carbon monoxide and carbon dioxide as the byproducts. Natural gas is usually the source of methane in this process. The less common production method is electrolysis which involves splitting water molecules using electricity. It’s uncommon because it’s very expensive.

Green hydrogen production means that the power for electrolysis is provided by renewable sources – mostly solar and wind power. Blue hydrogen is the moniker given to production using natural gas where the carbon byproducts are recaptured and stored. Both means of production are environmentally friendly, but they are dependent upon government subsidies to make the numbers work. The rug-pull for American production came from the Trump administration earlier this summer. Funding for major green and blue hydrogen production was dramatically curtailed.

Like the roommate holding your hair back while you heave into the toilet, shareholders recognized that the Cristal was a seriously bad idea. A proxy battle led by Mantle Ridge Capital resulted in the replacement of three directors and the installation of a new CEO early in 2025. Eduardo Menezes, who replaced the octogenarian Seifi Ghasemi at the helm, wasted no time shutting down three green and blue hydrogen joint ventures in California, New York and Texas which resulted in a $3.1 billion write-off.

Ironically, nine years ago, Ghasemi had been installed by Mantle Ridge. By 2025, the worm had turned. Mantle Ridge is led by Paul Hilal, an activist investor who may be more famous for his tenure at Pershing Square with Bill Ackman. I first learned about Hilal while reading the highly entertaining autobiography of Hunter Harrison, Railroader. Harrison was a force of nature, and he revolutionized the railroad industry.

Pershing Square’s 2012 activist campaign for Canadian Pacific was arguably one of the finest investments in modern market history. While Ackman grabbed the headlines, it was Hilal who worked the numbers and recruited Harrison – already an industry legend – to western Canada. People said you could never get CP’s operating ratio below 60% because of the mountainous terrain. Harrison did it, and more.

So, when I see Hilal’s involvement with a company it comes with serious gravitas. The man knows how to generate shareholder value. The question now becomes, has Air Products mired itself so deeply in unfeasible green and blue hydrogen projects that its future profitability is in doubt?

I think the answer is yes. Menezes and Hilal have a long road ahead of them. While the Louisiana project may turn out to be a winner, the Saudi Arabian green hydrogen investment seems destined for trouble. Air Products has a 30-year offtake agreement for the ammonia expected to be produced by the project. While they have obtained a take-or-pay commitment from TotalEnergies for a third of future production, the lack of foreseeable sales is a dark cloud on the horizon.

The Saudi project is known as NEOM Green Hydrogen (NGHC), and it is breathtaking in its ambition and lack of market potential. A joint venture between Air Products and Saudi power companies, the massive site on the Red Sea will have 4 gigawatts of solar and wind power. By 2027, the venture is expected to produce 1.2 million metric tons of green ammonia per year. The ammonia is useful for fertilizer production, but it also aims to become a source of clean fuel.

Scientists have yearned for a hydrogen power solution for decades. A hypothetical pipeline route was drawn for Europe during the 1970’s. Many scientists regard hydrogen as the holy grail of clean energy (all that water!), yet production is economically unfeasible without massive government subsidies. Transport and storage is highly complicated and unproven.

Nobody delivers the sobering truth about the lack of viability for green hydrogen better than Michael Liebrich. His keynote address at the Hydroverse Convention earlier this year…Ouch… Well, let’s just say the audience wasn’t enthusiastic.

NGHC is one of the industrial centerpieces of the futuristic master-planned development known as Neom. The vision, led by the Saudi crown prince, is to build a modern city of over a million people with a cost of over $1 trillion. It is designed to showcase the kingdom’s transformation away from fossil fuels and act as a technological innovation hub for the region. Already well over budget, the project has been scaled back. Yet NGHC moves forward, and construction is nearly 80% complete.

Air Products will tell you that you shouldn’t worry about NGHC because the financing in non-recourse. If that helps investors sleep at night, remember that this is a country that once held several errant business leaders captive at the Riyadh Ritz-Carlton for several weeks. Is there really such a thing as non-recourse when it comes to Saudi Arabia? You get a strange feeling when you watch Cristiano Ronaldo talk about playing soccer in his adopted land. Like maybe his soul has left his body. I had the same sinking feeling watching the Saudi national anthem played before the Bud Crawford fight.

Air Products is all-in on Louisiana and all-in on Neom. Economics be damned.

Air Products’ share price rallied after the boardroom coup d’etat. Investors seem placated by the choice of Menezes and they hope the steady returns of the past can be replicated once the new projects come online. After all, a 15% return on the $17 billion of green and blue hydrogen investments would effectively double current levels of net income which amounted to roughly $2.8 billion over the trailing twelve-month period.

Failure to deliver, however, and the company faces years of painful asset write-downs and a debt hangover. With few customers for Saudi green hydrogen on the horizon, the latter prospect seems more likely.

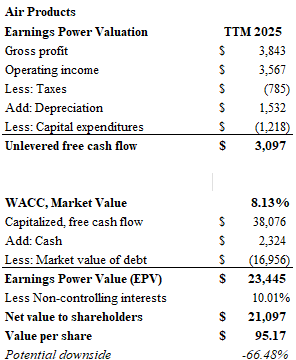

I present two valuation models below. The first is an earnings power valuation. The simple approach is advocated by Bruce Greenwald, heir to the Columbia value investment lineage that descends from Ben Graham. The model for EPV is simple. Take normalized free cash flow, or “owner’s earnings” in Buffett’s parlance, and divide by the weighted average cost of the firm’s capital.

The major limitation with the Greenwald method is its inability to account for growth. It takes the past results and capitalizes them, making no calculations for the future.

Value investors are a lonely bunch. The market has moved on. In a world trading on vibes and memes, the value investor is as quaint and archaic as the old boys’ club in the first paragraph. One could take a shot at projecting cash flows into the future and discounting them to the present. But the future is so uncertain. So someone from the value investment world needed to step up and properly account for a company’s future growth.

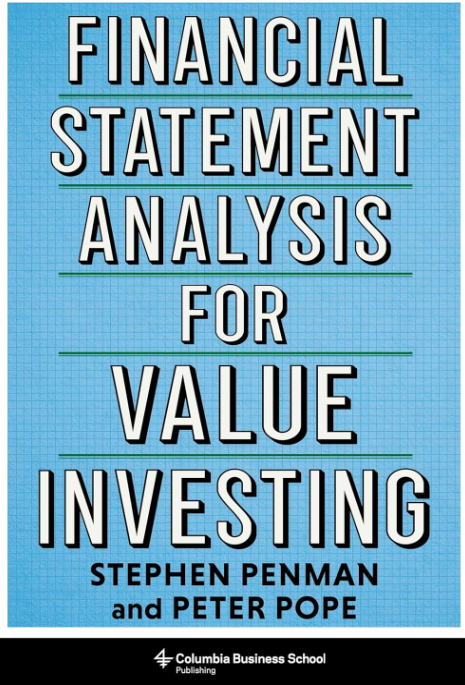

Into the breach stepped Stephen Penman and Peter Pope, again of the Columbian tradition. Their book Financial Statement Analysis for Value Investing (Columbia U. Press, 2025), is an excellent addition to the canon. They are accountants, and they contend that growth is only valuable to the extent that future earnings exceed a hurdle rate of return. If a company’s net earnings represent a 12% return on the company’s book equity, and the hurdle for such a company is 10%, then one can figure that this additional 2% is where real value is created.

They take the book value of the company’s equity and add a capitalized value for these residual or surplus earnings. Growth is factored in the denominator. The higher the growth, the lower the denominator, the higher the residual value.

A value investor can solve for the growth rate to see if a price makes sense. They offer a compelling example of Buffett’s purchase of Apple. At the time, in 2016, solving for the “g” in the growth portion of the equation showed that Apple’s price anticipated only a 2% growth rate. It was certainly a safe wager to think that Apple could manage better than 2% growth.

The problem with the model is that the authors don’t have much of an answer for the hurdle rates they choose. Yes, they spend several pages talking about risk and leverage, but ultimately they settle on the investor’s preference. The reader craves Damoradan’s rigorous precision. Penman and Pope (and Munger and Buffett) scoff at complicated equations. Precision can be precisely wrong. They would probably contend that its better to have that margin of safety in a 12% hurdle rate for a risky venture, than calculate some kind of Frankenstein-WACC with beta at its core.

The earnings power valuation (EPV), a zero-growth model, indicates that APD may be worth less than $100 per share. This would mark a 66% decline from current levels. In this model, unlevered free cash flow is divided by a weighted average cost of capital of 8.13% to arrive at a value of $23.5 billion after subtracting $14.6 billion for the market value of net debt.

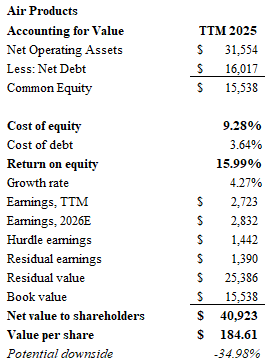

The “accounting for value model” or “Penman-Pope Model” is a lot more forgiving because it makes an accommodation for growth. We start with the base. Penman and Pope frequently ask the reader to “take the balance sheet with you.” Here we use the book value of equity, $15.5 billion, as the first half of the equation.

The second half of the equation is determining residual earnings for the following year. In this case, I simply increased trailing twelve-month earnings by 4%. This may be slightly hopeful, but its not unreasonable. Note: unlike the unlevered cashflows of the EPV model, earnings are net of debt expenditures. The “hurdle” I set for Air Products was 9.28%. This is the 10-year treasury yield, plus a spread for the company’s A-rated debt, and an additional 4.33% equity risk premium.

Air Products delivered a 16% return on equity for the TTM 2025 period, so the residual earnings – the amount above the hurdle – is $1.4 billion. The figure is divided by a denominator of r – g where r is the 9.28% cost of equity less a proxy for growth. In this case I used 4.27% (the 10-year Treasury yield). The residual value is approximately $25.4 billion. Added to book value, the sum is $40.9 billion or about $185 per share. This represents a level 35% below the market price.

The aspect of the model that is appealing, is that it allows one to see whether growth is reasonable. In other words, what level of growth would justify today’s price of $283 per share? The answer is 6.6%. If you think world demand for hydrogen meets or exceeds this level, you would conclude that Air Products is fairly valued.

So, these are just my estimates and they are certainly crude. I don’t make any attempts to understand the potential demand for green hydrogen in Europe or the possibility that production costs could be dramatically reduced through lower energy inputs from solar power. I certainly would think twice before betting against Paul Hilal.

However, despite our best intentions to improve the environment, the efforts at carbon recapture and electric hydrolysis have relied heavily on government subsidies. As governments reckon with yawning fiscal gaps and a need to re-arm for global conflicts, it seems likely that the green ammonia produced in Saudi Arabia lacks an end-market. The uncomfortable meetings in the Air Products boardroom could persist for many years as assets are written-down and debt service gnaws away the bottom line.

Until next time.

DISCLAIMER

The information provided in this article is based on the opinions of the author after reviewing publicly available press reports and SEC filings. The author makes no representations or warranties as to accuracy of the content provided. This is not investment advice. You should perform your own due diligence before making any investments.

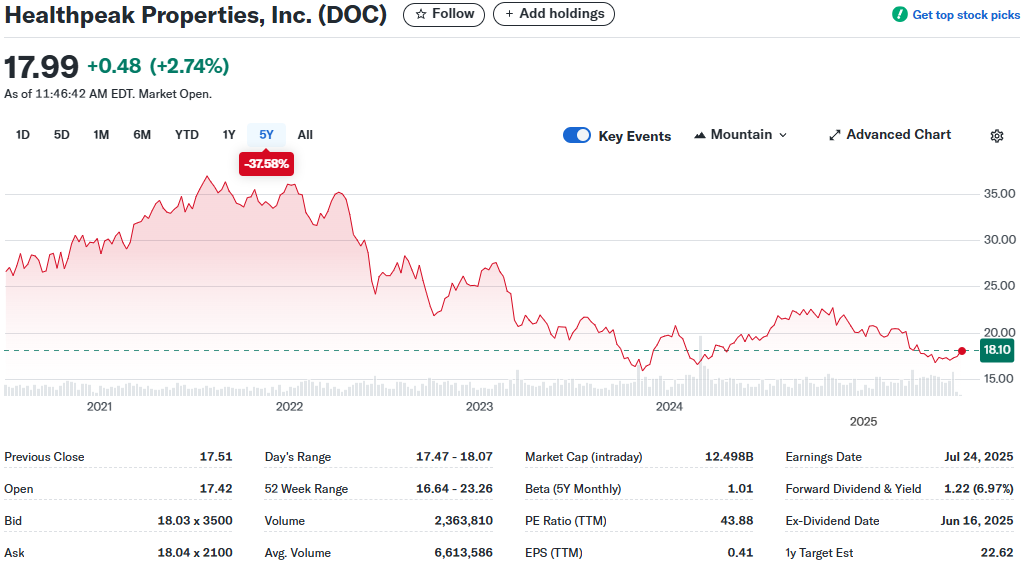

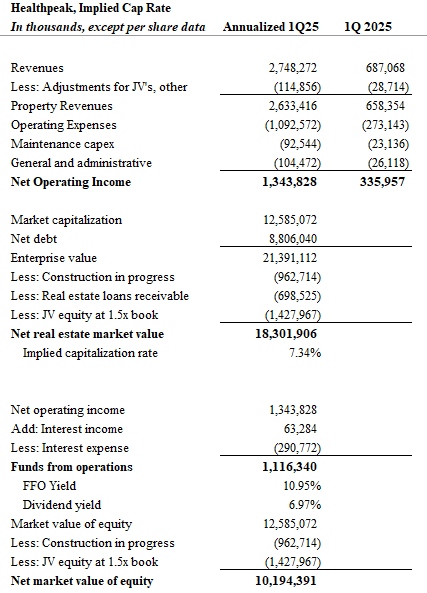

I don’t have much time this week, so I’m in shallow water. I’ve got a little back-of-the envelope one for you. Healthpeak Properties Trust (DOC) is a Denver-based owner of outpatient medical buildings and lab space. The company merged with Physicians Realty Trust in 2024. The stock has not performed well, but the 7% dividend yield is very enticing. DOC trades with a market cap of $12.5 billion.

The dividend seems well-covered, however the lab space (31% of revenues) is a wildcard. There has been an incredible amount of new supply, and the biotech market isn’t exactly robust. Despite the risks, this one deserves a closer look.

For now, here are my rough numbers. I am taking a leap of faith by annualizing just one quarter for the balance of 2025. The stock trades with an FFO yield of approximately 11%. I subtracted maintenance capital expenditures (taking management at face value) from net operating income, and it appears that the real estate trades for an implied cap rate of 7.3%. This seems pretty high, but it probably reflects the risks associated with lab space tenants. Leverage is also a little higher than I’d prefer, but the maturity timetable appears manageable.

The problem with Healthpeak, and so many other office REITs for that matter, is “what does upside look like?” How does this story improve? It’s not like the National Intitutes of Health is going to start writing grant checks for new clinical trials any time soon. Healthpeak doesn’t have the ability to refinance debt any more cheaply than what’s on its books today.

Beware the siren song of high dividend yields. Usually the market knows something about risk that you don’t. If you’re just buying debt with a single-B credit rating, you should definitely receive more than 7% on your money. The “equity” may not be worth more than a similar junk bond.

Until next time.

DISCLAIMER

The information provided in this article is based on the opinions of the author after reviewing publicly available press reports and SEC filings. The author makes no representations or warranties as to accuracy of the content provided. This is not investment advice. You should perform your own due diligence before making any investments.