Many years ago, when I was in high school, my Dad gave me some scholarly advice that paid dividends in subsequent years. He said that if I was stumped on an essay question, then the best thing to do was to “show what I know”. I may not have all the facts about the Battle of Antietam, but I might be able to muster some pretty decent paragrpahs about why Abraham Lincoln demoted General George McClellan. “Show what you know” snatched mediocrity from the flames of academic despair on several occasions.

That’s where I’m at this week. I don’t have any new conclusions, but I can tell you a few of my thoughts and observations. Here’s to showing what (little) I know…

Peakstone Realty Trust (PKST)

Oh Peakstone, you broke my heart. Last fall, I thought I found the ideal REIT trading at an enormous discount. Peakstone was priced in the $14 range and had a market cap of $480 million. The office and industrial REIT owns some prime property like the Freeport McMoRan tower in downtown Phoenix, Amazon distribution centers, and the McKesson office complex in Scottsdale.

I threw a ludicrous cap rate at the office space and figured the real estate was still worth about $1.7 billion. After subtracting net debt of $936 million, I thought the stock was worth $18. Plus it had a 6% yield.

We’re now 40% lower, and that stings. A lot. All management really had to do was buy back stock, sell assets and pay down debt. When your dividend is yielding 6%, it’s a no-brainer. Instead, deal junkies do what deal junkies gotta do. Deals, y’all. In November, they went out and re-levered the balance sheet in to buy a $490 million portfolio of outdoor storage real estate at a cap rate of… 5.2%.

I did not have buying B industrial assets with negative leverage on my bingo card, but there you go. The website photos on Peakstone’s portfolio page now look like the opening credits from Sopranos.

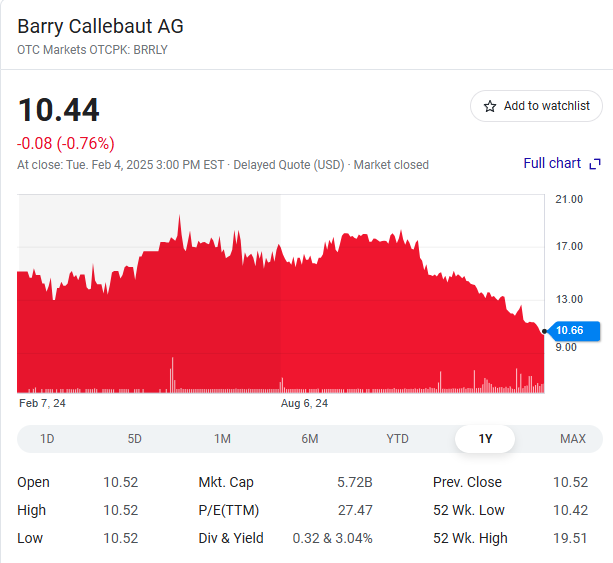

Barry-Callebaut (BRRLY)

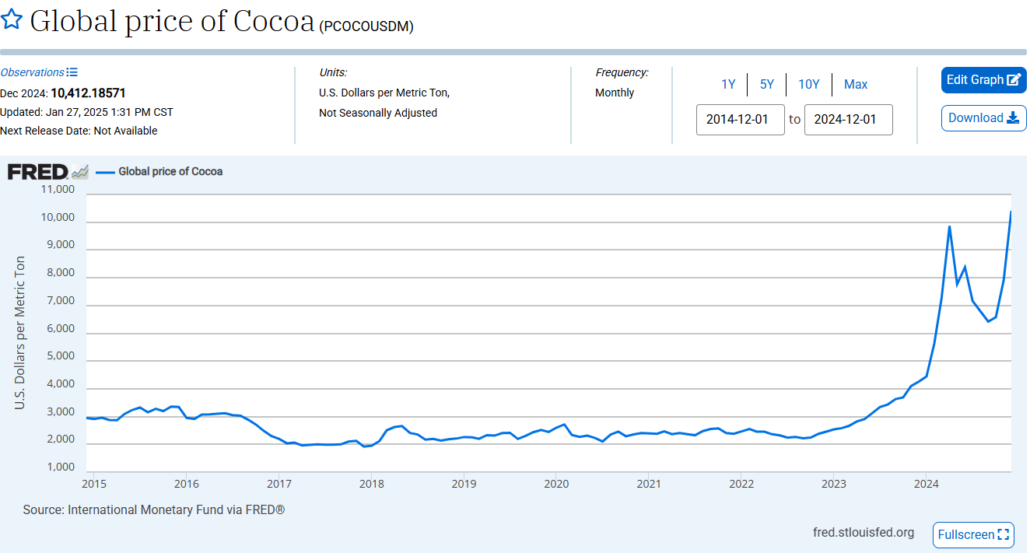

The Zurich-based refiner and seller of chocolate has taken an absolute beating as the price of cocoa has skyrocketed. Shares are down 50% over the past year. I’ve never seen anything quite like the price chart for cocoa. Parabolic is an understatement. It’s actually mind-boggling.

Crop failures in Ivory Coast and Ghana have led to a shortage. But is it really that bad? There’s got to be an opportunity here somewhere. Surely futures markets are way over their skis?

Barry-Callebaut is one of the leading suppliers to confectioners, and they have a dynamic new CEO who has begun an efficiency drive. The problem is that Barry-Callebaut had to purchase inventories of cocoa at massive discounts to the contracted sales prices to their customers.

Working capital looks like an absolute trainwreck. The company spent over 2.6 billion CHF on cococa inventory over the past year. In order to cover the loss, BRRLY turned to the debt markets and raised about 3 billion CHF. Eventually, the cocoa market’s gotta rebalance, right?

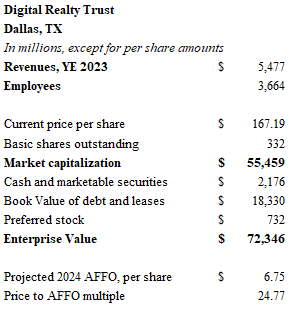

Digital Realty Trust (DLR)

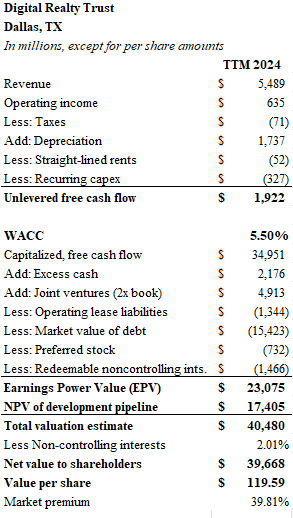

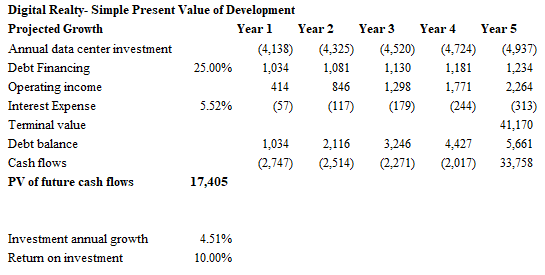

The sector is so hot right now. An Australian fund manager, Nate Koppikar, is shorting data centers in the belief that supply of will outstrip demand as this whole AI-thing bursts its bubble. I have looked at Digital Realty in some depth. I don’t have much of a smoking gun here, but I do agree that the market is way ahead of itself.

Digital Realty trades at 24 times projected funds from operations and carries an enterprise value of $70.4 billion. I produced a cocktail napkin set of numbers and my conclusion is that the stock trades at a 40% premium to its intrinsic value.

I took the most recent unlevered free cash flow of $1.9 billion and applied a cap rate of 5.5%. This results in an asset value of $35 billion. I subtracted debt, redeemable noncontrolling interests, preferred stock and added joint venture investments at 2 times book value. Next, I ran a very basic discounted cash flow on a future investment pipeline that essentially doubles the company’s real estate footprint in five years. I assumed 25% leverage for the new properties. The present value of future development amounts to $17.4 billion. The sum of these pieces is an estimate of net asset value of $39.7 billion.

Obviously, this is a work in progress, but here are my general observations thus far: REITs must distribute 90% of their taxable income. Therefore, it is very difficult to achieve growth through the reinvestment of profits. DLR pays a dividend yield near 3%, and this leaves virtually zero cash to deploy into new data centers. DLR must, therefore, raise external capital in order to grow. I assumed that they continue to borrow 25% of their future investment requirements. The rest needs to come from the issuance of new stock. Indeed, during the first three quarters of 2024, Digital Realty raised $2.7 billion by issuing new shares.

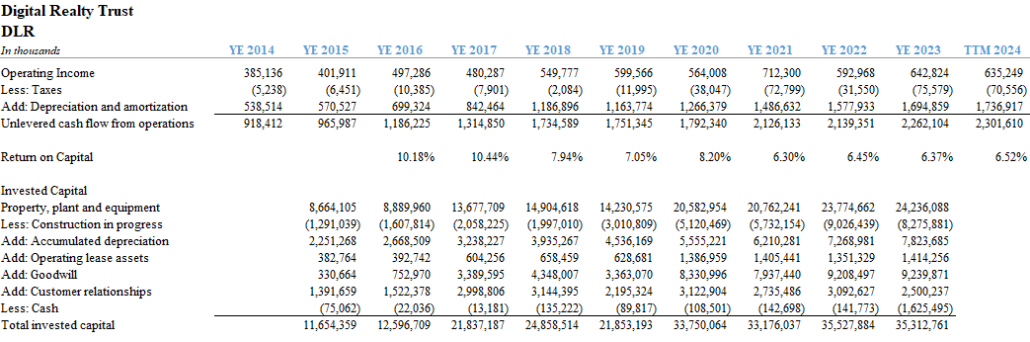

Raising cash through the sale of stock to deploy into profitable real estate developments works just fine as long as the return on capital exceeds the cost of capital. In this regard, DLR’s recent track record has been unexceptional. Returns on capital have hovered near 6.5%. In my future development scenario, I assumed returns of 10%. This is what their major competitor Equinix has been able to achieve. DLR has been able to produce shareholder value despite unremarkable asset performance because they loaded up with debt at the absolute bottom of the COVID-era interest rate bonanza. The weighted average cost of the $17.1 billion of loans outstanding is a puny 2.9%. Unfortunately, the incremental debt for the development program will have an interest rate in the 5% range.

At this point, I don’t have a strong conviction about the value of Digital Realty. My projections are too simplistic to be relied upon. But I do believe that the stock reflects a future development pipeline that must be executed flawlessly and at returns much higher than the company has a achieved in recent years. REITs that can issue stock, and deploy the cash at returns in excess of the cost of capital work very well. When they don’t deliver those returns, they become shareholder dilution machines. I’m going to leave it here for now.

Until next time.

DISCLAIMER

The information provided in this article is based on the opinions of the author after reviewing publicly available press reports and SEC filings. The author makes no representations or warranties as to accuracy of the content provided. This is not investment advice. You should perform your own due diligence before making any investments.

MASH was always full of laughs, but those CBS writers never let you forget about the senseless brutality of war. One minute the affable Colonel Henry Blake is on his way back from Korea to his wife and kids, the next minute he’s gone. Radar runs into the triage tent to tell everyone the news. Gut punch.

So goes Hollywood. Blake’s actor, McLean Stevenson, wanted more screen time. Fed up, he asked to be released from his contract in 1975. CBS obliged. I’m sure McLean Stevenson appeared in other roles. I can’t tell you what those were.

We don’t like to admit so much in life comes down to luck. It has to be skill, knowledge, expertise or “God’s plan”, right? There must be an explanation.

But sometimes luck really is the answer. Henry Blake lands in Tokyo. McLean Stevenson gets cast as Mr. Rourke on Fantasy Island.

Sure, you can put yourself into a lucky positions. Sam Zell’s father knew the Nazis were coming for his family. He prepared. He moved assets. He fled Poland. He also just happened to catch the last train out before the Luftwaffe bombed the tracks.

America has had a lot of lucky breaks. In the War of 1812, England was on the verge of reclaiming her colonies. Washington, DC was under siege by the British army. After the White House burned to the ground, a great tornado struck the Potomac valley. The British fled.

But we’ve gone too far. We’ve turned into a nation of degenerate gamblers. It’s not enough to go to a casino down the street or have an online sports betting app on your phone. You can trade memecoins! Just buy stock in quantum computing companies with no viable way to profitability. Or, you can roll your entire net worth into triple-levered Nasadq QQQ ETF’s. You’ll be fine. Stop-loss orders always get filled in a market panic.

That’s why value investing appeals to me. There is so much luck, chance and uncertainty involved in business. You can’t know the future. But you can hope to find companies that are selling at a price with a margin of safety – they appear to have some protection from downside; from bad luck and all of its cousins.

The most unlikely place to find good companies selling for reasonable prices is Hong Kong. As unbelievable as that sentence may read, it was not generated by Co-Pilot. Two weeks ago, I wrote about the bargain price for Johnson Electric (JEHLY), and briefly mentioned Budweiser APAC (BDWBY) and Sinopec Kantons (SPKOY). This week I am recommending WH Group (WHGLY).

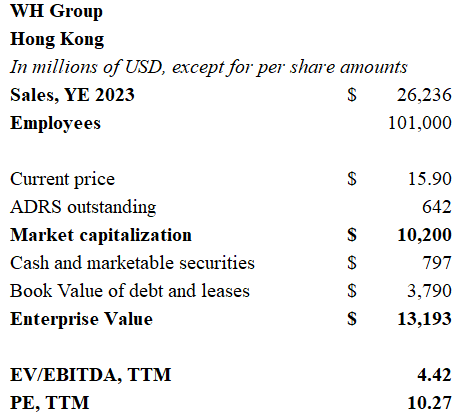

WH Group is the world’s largest producer of pork. The stock trades on the Hong Kong bourse and can also be bought over the counter at about $15.90 per share. The company had revenues of $26.2 billion in 2023 and $25.4 billion over the last twelve months’ reporting period through June of 2024. China and Europe accounted for 39% of WH Group’s 1H2024 revenues, and 46% of operating profits. The company was unfazed by the pandemic, instead it suffered it’s worst financial results during 2023 when pork prices in North America collapsed causing major inventory write-downs at the Smithfield division.

WH Group purchased the Virginia-based Smithfield for $4.7 billion in 2013. Now, WH Group plans to-relist Smithfield in a share offering. The projected value of the Smithfield operation is $10.7 billion. As part of the IPO, WH Group will reap about $540 billion in cash and reduce its ownership stake from 100% to 89.9%.

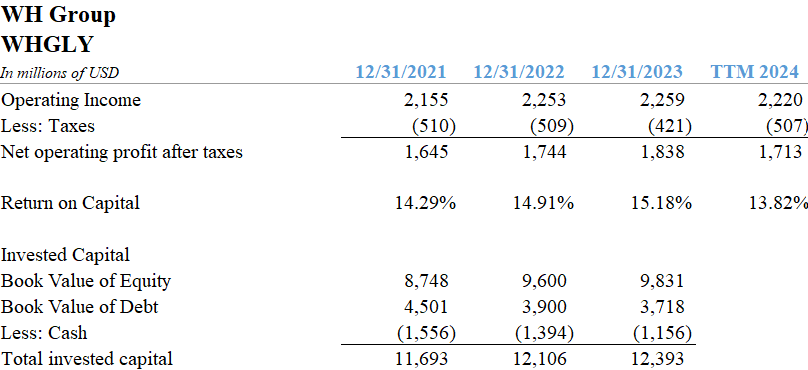

WH Group trades with a trailing PE of 10.4 times earnings and pays a substantial 5.6% dividend yield. The company is rated BBB by Standard & Poor’s, carrying a modest $3.8 billion of debt and operating leases with a weighted average interest rate of 4.4%. Gross margins are in the 19% range, with net margins above 8.5%. Returns on capital have been between 13% and 15% in recent years which seems noteworthy for a food processor.

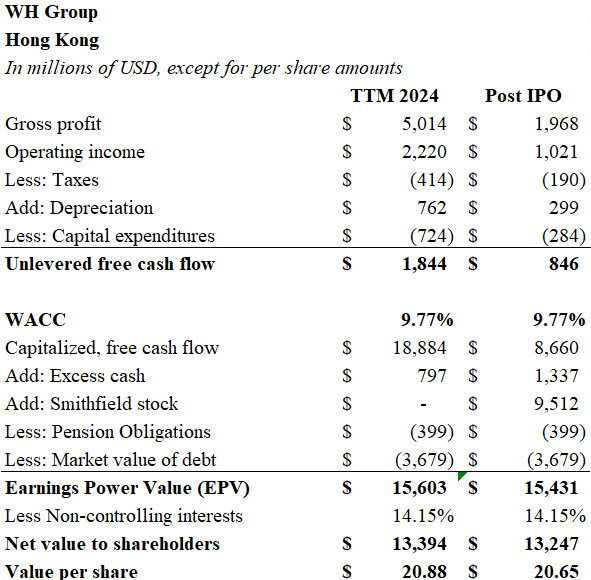

By my calculations, WH Group has more than 23% upside. Unlevered free cash flow for the company exceeded $1.8 billion over the trailing-twelve month reporting period. Employing a weighted average cost of capital of 9.77%, gives WHGLY a value of $18.9 billion. Adding $800 million of cash but subtracting the debt and about $400 million of pension obligations leaves an earnings power valuation of $15.6 billion. Adjusting for non-controlling interests, WH Group is worth about $13.4 billion, or $21 per American share. The effect of the Smithfield IPO is also presented below.

There are plenty of caveats. WH Group is listing its Smithfield operations because they have an opportunity to raise some cash, but the political optics are important. Distancing China from the US food chain is probably a well-caulculated move to insulate the company from US criticism. Second, WH Group has already run up by about 30% over the past 12 months. The really low-hanging fruit has been plucked. Finally, the Chinese economy is suffering a dramatic downturn as the property market hangover sets in. Consumers are in a frugal mood. Eating less pork may be a way for Chinese households to economize.

The Smithfield IPO will be a landmark moment for WH Group. If the North American operations receive a $10.7 billion stamp of approval by American investors, it could lead investors to ascribe a higher multiple to the Chinese and European businesses.

Until next time.

DISCLAIMER

The information provided in this article is based on the opinions of the author after reviewing publicly available press reports and SEC filings. The author makes no representations or warranties as to accuracy of the content provided. This is not investment advice. You should perform your own due diligence before making any investments.

My sister and I always knew it was a big deal when Dr. Sidney Freedman showed up on MASH. The psychiatrist wasn’t there to join the wise-cracking banter in the triage tent. And he sure wasn’t going to put on dresses with Klinger or pull pranks on Dr. Winchester. Somebody was about to get their psychological puzzle dis-assembled right there on national television.

In the final seasons of the comedy show’s 11-year run, MASH explored some dark territory. Even though MASH was set during the Korean War, just about everyone knew it was really about Vietnam. As the series went into its last few years, CBS seemed to stop pretending. Alan Alda’s hair grew pretty long, and so did his dramatic scenes.

Not only was it ground-breaking to put a psychiatrist on television in the 1970s, the writers gave him the rank of major. Dr. Freedman outranked the surgeons, BJ and Hawkeye. CBS seemed to be asking a generation of Americans burdened by the Vietnam era the ultimate question: What good is fixing a broken body if you can’t heal the soul?

It was actually our mother who clued us in to Dr. Freedman. Mom took a keen interest in Sid, just like she preferred the wit and charm of John Chancellor to the gruff Walter Cronkite. Mom had a master’s degree in social work, so Sid was her kind of people. Yep, when Dr. Sidney Freedman came to the camp, we knew it was time to go deep.

Having a mother with an MSW was like having Dr. Sidney Freedman right in our home. Well, in Mom’s case, it was more like a combination of Sid plus a mixture of Helen Reddy and Maria from Sesame Street. The childhood distress of silent treatments from girls in the classroom, peer pressure, embarrassment about acne – Mom was always ready with the right words. “Maybe they’re being mean because of their own insecurities”. Thanks, Mom!

They could make a modern spin-off of MASH with Dr. Sidney Freedman as the lead character. Only this time he wouldn’t be a shrink in a military hospital unit, he’d be running a private credit firm. Preferably one named for a Greek or Roman god. “Welcome to my office. Make yourself comfortable. Some of my clients sit, but most prefer to lie on the SOFR.” This script practically writes itself. It would be like having Dr. Wendy Rhoades on Billions, only better.

You need to have a degree in psychology to understand today’s markets. The keen ability to diagnose and treat delusional thinking is a prerequisite. Consider this: an electronic token generated by a computer algorithm has reached a price of $100,000. The “currency”, invented by Satoshi Nakamoto in 2008, is backed by no government and has few nodes of exchange except for illicit activities. Who is Satoshi Nakamoto? To quote Nate Bargatze, “Nobody knows.”

Let’s take it a step further. There is a company called MicroStrategy (MSTR). It is nominally a software business, but it really has only one purpose. It issues shares in the company to the public for which it receives old fashioned United States dollars. These dollars are backed by the world’s most powerful military, the largest economy, and is recognized around the globe as “legal tender for all debts public and private”. But instead of putting these dollars to work as investable capital for economic production, what does MicroStrategy do? It simply turns around and uses the real dollars to purchase electronic “crypto currency”.

MicroStrategy now owns $43.4 billion of this digital currency. Logic would tell you that the value of this company should be in the neighborhood of, say, and I’m just guessing here… $43.4 billion? Nope. The company trades with a market cap of $80 billion. “Investing” in MicroStrategy means that you are paying $2 to receive $1. And that $1 may not even actually be $1 because its digital money invented by some random guy with a computer in 2008.

There is a paragraph that I came across recently that seemed to leap from the page. Looking back from their perch in 1940, Benjamin Graham and David Dodd made this observation in Security Analysis: “The advance of security analysis proceeded uninterruptedly until about 1927, covering a long period in which increasing attention was paid on all sides to financial reports and statistical data. But the “new era” commencing in 1927 involved at bottom the abandonment of the analytical approach; and while emphasis was still seemingly placed on facts and figures, these were manipulated by a sort of pseudo-analysis to support the delusions of the period.”

Pseudo-analysis? Here’s another head-scratcher. Let’s see if we can understand the concept called “Yield Farming”. Yield farming is a high-risk investment strategy in which the investor provides liquidity, stakes, lends, or borrows cryptocurrency assets on a DeFi platform to earn a higher return. Investors may receive payment in additional cryptocurrency.

Got it?

Yield farming sounds very sophisticated. It also sounds an awful lot like something Charles Ponzi would have invented were he alive in 2025 instead of 1925. If you prefer time traveling to 1635 Amsterdam, you could easily replace the word “cryptocurrency” with “tulip bulb”. For those of you earning such a high return, I wish you well. When the music stops, someone will be holding an empty bag.

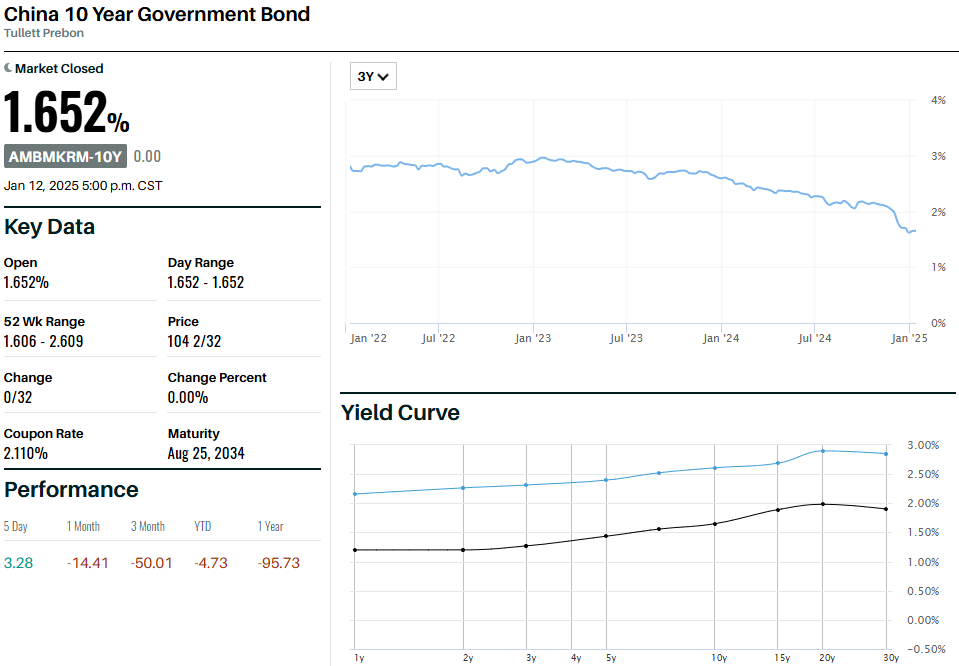

The hunt for rational market prices has led me to Hong Kong. Don’t laugh. The Hang Seng index is down by about 17.5% since its October-2024 peak. Fears of a Chinese debt-deflation spiral have begun to make the headlines as 10-Year Chinese bond yields have tumbled to 1.65%. China has too much real estate, not enough population growth, and massive levels of government debt at the local levels where municipalities became far too dependent upon the real estate market.

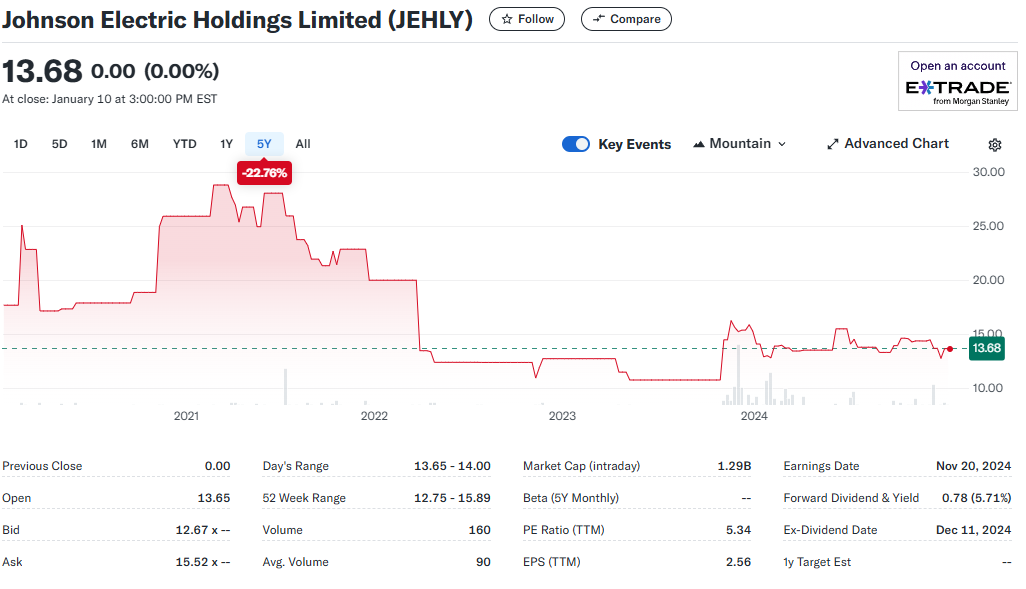

Amid the gloom, there are bargains to be found. Earlier, I wrote about the major discount to book value on offer at CK Hutchison (CKHUY). Meanwhile, Budweiser APAC (BDWBY) trades for 14 times earnings and pays a 6% dividend yield. The oil refiner, Sinopec Kantons (SPKOY) can be bought for a PE of 7.6 yielding 6.58%. But Johnson Electric is the biggest bargain of them all.

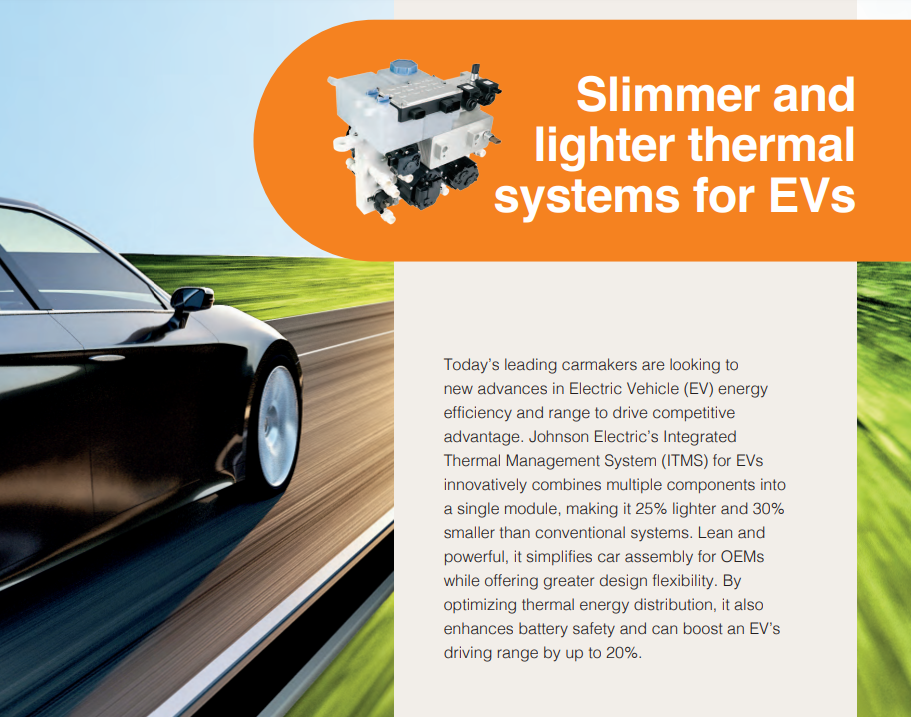

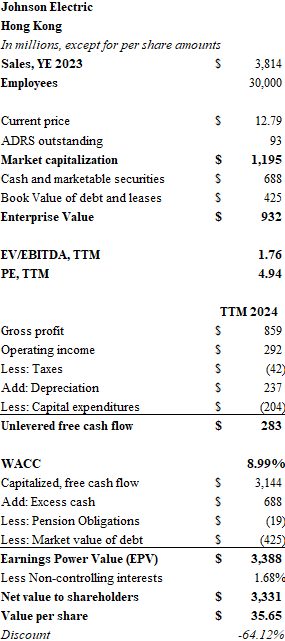

Johnson Electric (JEHLY) shares are valued at $1.2 billion by the market, trading hands at a price-to-earnings ratio below 5x for the trailing twelve-month period ending September 2024. The Hong Kong-based maker of small electrical motors racked up sales of $3.8 billion for the fiscal year which ended in March of 2024. Sales declined over the most recent 6-month period compared with 2023, but gross margins expanded from 22.2% to 23.6% resulting in gross profits over the trailing twelve months at $859 million. Net margins are in the 7.5% range, and operating income for the 12-month period amounted to $292 million.

Johnson Electric makes small motors which are an integral part of the automotive, factory automation, life sciences, and HVAC sectors. The automotive sector accounts for 84% of sales and therein lies the rub. Peter Lynch often warned about buying cyclical companies with low-PEs, and the current cycle may not be favorable for autos. Interest rates in much of the West have placed auto affordability beyond the reach of most consumers, and China faces a possible oversupply problem in its domestic EV market.

Johnson Electric can weather a cyclical downturn. The company was started by Mr. & Mrs. Wang Seng Liang in 1959, so this won’t be their first rodeo. The balance sheet is strong. Nearly $700 million of cash offsets the $425 million of debt. The company is rated BBB by Standard & Poor’s. PricewaterhouseCoopers is the auditor. Johnson Electric has over 1,600 customers with sales split roughly by thirds between Asia, North America, and EMEA. Over 30,000 employees manufacture more than 4 million products per year in factories across the globe.

The stock is exceptionally cheap. Unlevered free cash flow over the most recent 12-month period was approximately $283 million. Using a weighted average cost of capital of 9%, the earnings power value exceeds $3.1 billion. Deduct net debt and some pension obligations, and the intrinsic value of the equity is $3.3 billion or $35.65 per ADR. The current market price represents a 64% discount. The market value is a whopping 50% discount to book value. Meanwhile, the 5.7% dividend yield seems well-covered.

Johnson Electric may be in the early days of a difficult downturn for the global auto sector. The saber-rattling between China and Washington certainly isn’t helpful. Despite these concerns, a 60% discount represents a massive margin of safety. I will be adding Johnson Electric to my portfolio.

DISCLAIMER

The information provided in this article is based on the opinions of the author after reviewing publicly available press reports and SEC filings. The author makes no representations or warranties as to accuracy of the content provided. This is not investment advice. You should perform your own due diligence before making any investments.