In 1990, Jeremy Irons won an Oscar for his portrayal of the mercurial and debonair Claus Von Bülow in Reversal of Fortune. Von Bülow captured tabloid headlines for the attempted murder of his Newport socialite wife, Sunny (Glenn Close). The case seemed hopeless. Only Claus had access to the insulin that left Sunny in a diabetic coma. Evidence was only part of the problem. Claus was not exactly a warm and fuzzy guy. With his angular chin and vaguely European accent, the ascot-wearing Von Bülow was aloof and arrogant. Against the odds, the young professor Alan Dershowitz (Ron Silver) and his earnest team of Harvard Law students delivered a stunning acquittal.

At the end of the movie, Claus sits in the back of his chauffeur-driven Jaguar as Dershowitz bids him farewell, saying: “You know, it’s very hard to trust someone you don’t understand. You’re a very strange man.” As the door closes, Von Bülow deadpans, “You have no idea.”

“Strange” is subjective, of course, and context matters. Claus was probably a normal guy if your scene was 1970s ski chalets in Gstaad. To a working class jury in 1980s Rhode Island, he was eccentric.

If you’re on the artificial intelligence bandwagon, everything might seem pretty normal right now. Short term interest rates are coming down and we may be on the cusp of a new information technology miracle. In this exuberant era where the NASDAQ sets new records nearly every day, Omaha’s Warren Von Büffett seems strange. After all, he’s sitting on $240 billion of T-bills. Imagine selling all that Apple stock right when this AI thing is just starting to take off!

What’s strange? What’s normal? I like Jodi Picoult’s thoughts on the matter: “I personally subscribe to the belief that normal is just a setting on the dryer.” Ms. Picoult usually digs deep into matters of the heart, but she could just as easily be opining on the current state of financial markets.

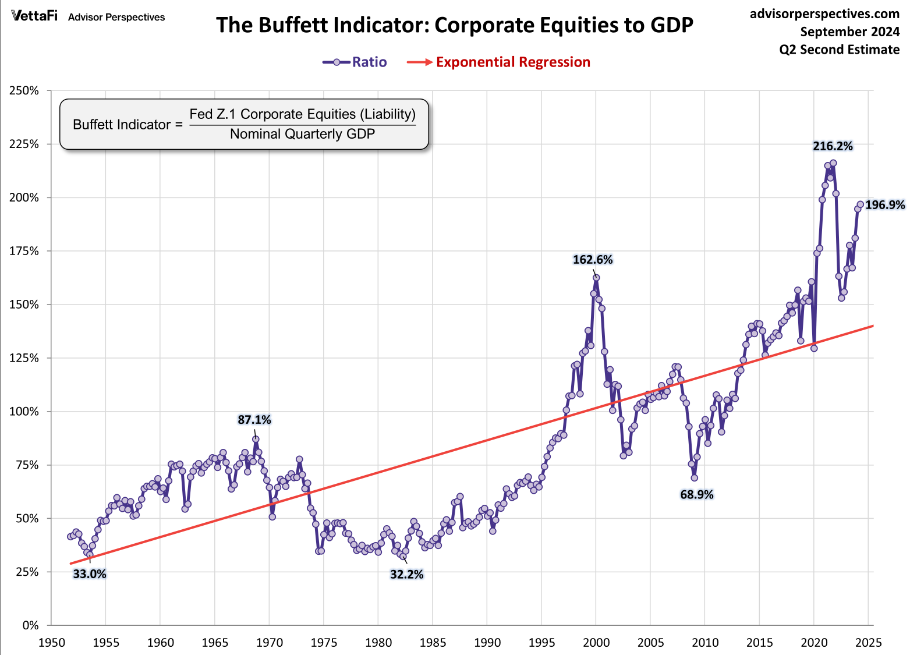

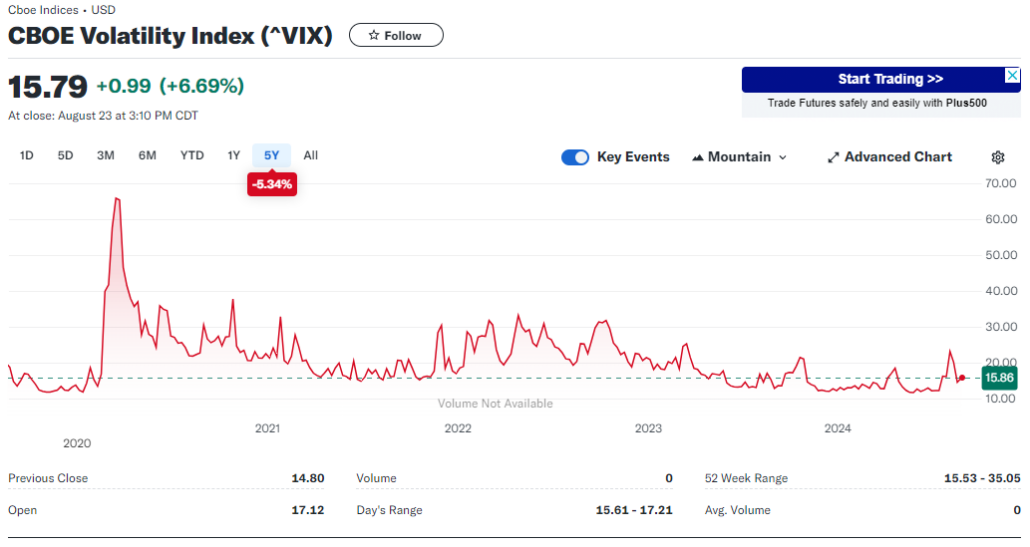

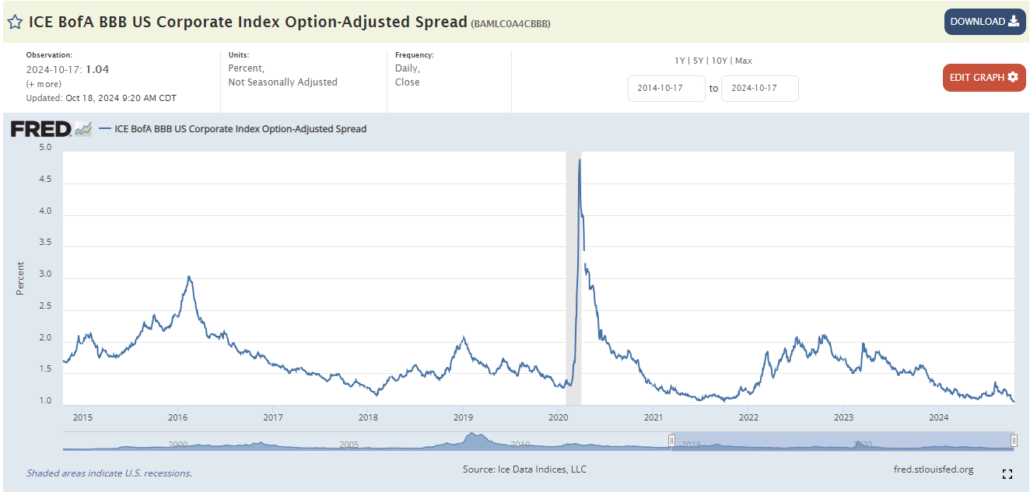

The value of corporate equities as a percentage of GDP has only been this high two other times. While most of us mortals must pay our debts by forking over cold hard cash to the lender, huge numbers of heavily indebted firms are paying their interest bills by issuing IOUs. You need to squint to see the spreads on corporate bond yields. It turns out that nearly losing one presidential candidate to assassination, and the other to dementia doesn’t have much of an effect on markets. Did I mention there are two wars with nuclear implications going on? How about the collapse of the world’s second largest housing market? Nope, hold my beer because the QQQs keep ripping higher.

I remember the Three Mile Island meltdown. It was not an auspicious moment in American history. We had kind of a Jimmy Carter-malaise thing going down, and our status on the world stage was being put out to pasture by Ayatollah Khomeini. We couldn’t even manage nuclear power plants very well. When they said we’re re-starting Three Mile Island again because we need so much power to run these AI chips, my bullshit detector issued an alert. 🚩

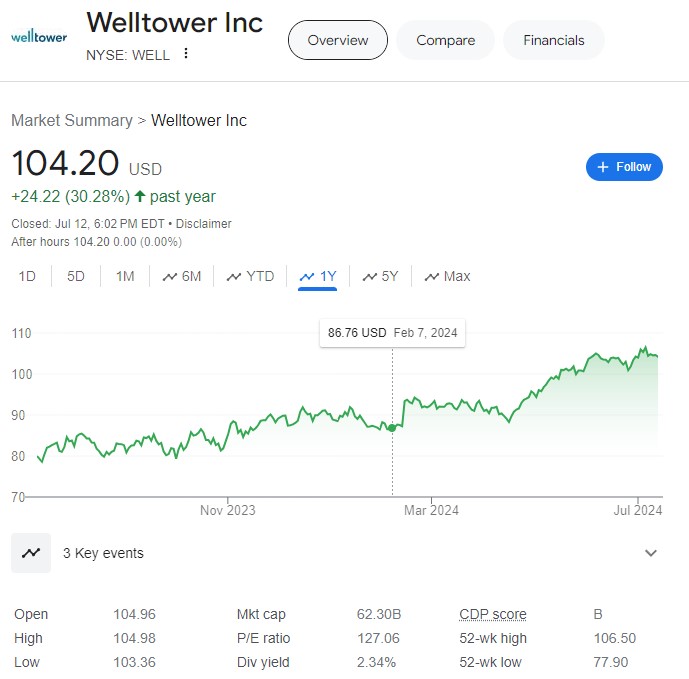

Welltower (WELL) is a company that Claus Von Bülow might prefer: Very strange, indeed. Welltower stock behaves like it belongs among the exalted world of artificial intelligence – surging ahead by 45% over the past six months alone. Given the levitating stock price, it probably shouldn’t come as a surprise that Welltower’s CEO quoted Jensen Huang in his last shareholder letter. The excitement fades pretty fast when you realize that Welltower operates in the staid world of housing elderly folks.

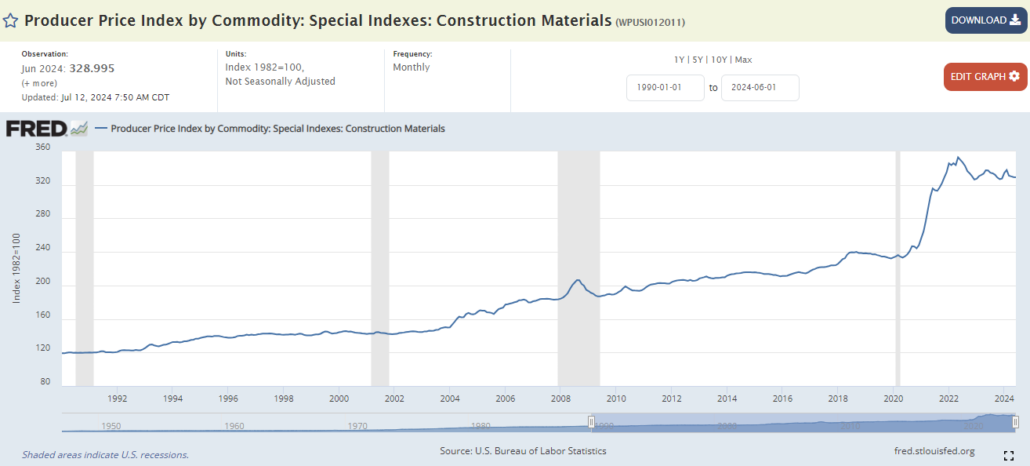

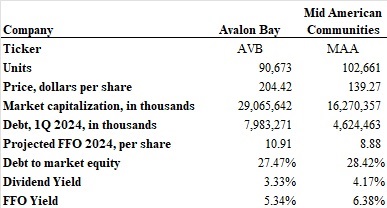

While other senior living companies trade within a justifiable range of the value of the underlying assets, Welltower seems divorced from reality. By my reckoning, the company trades at a premium of over 40% to its underlying bricks and mortar. Welltower is a Toledo-based owner of senior living facilities that trades at a market capitalization of over $80 billion, or $132 per share. However, a reasonable valuation of the real estate indicates that the stock should trade closer to a level of $50 billion. That computes to a share price near $80.

As a real estate investment trust (REIT), Welltower is required to pay out most of its earnings as shareholder distributions. Yet the yield on offer is a paltry 2%. Growth can only be achieved by adding external capital, and Welltower has issued billions of dollars in new stock since the debt markets became less hospitable. In December 2022, the company also gained the dubious distinction of a write-up by Hindenburg, the famed short-seller, for questionable dealings with the mysterious Integra Health Properties.

Moreover, Welltower is not a simple business. WELL has a complex collection of disparate facilities throughout the country operated by a diverse set of managers. Many facilities are net-leased to other operators leaving Welltower the simple role of cashing rent checks as a landlord. Many others are operated hands-on by the company. Looking after the elderly is a tough business. You need skilled medical staff to run these properties in addition to a legion of cleaners and minders. The government is constantly looking over your shoulder (especially after the whole Covid fiasco), and Medicare money comes with strings attached.

Welltower also acts as sort of a bank for senior housing developers, with over $1.7 billion of notes receivable on the books. To complicate matters further, WELL also owns a collection of outpatient medical clinics.

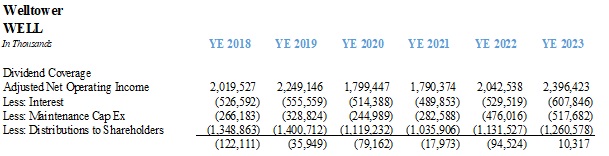

There are certainly many reasons to praise Welltower. The company disposed of $5 billion of struggling assets during the dark times of Covid, and rebounded with a $10 billion acquisition frenzy over the past three years. Welltower added another $2 billion of development during that time. In 2023, operating income (including depreciation) increased by over 30%.

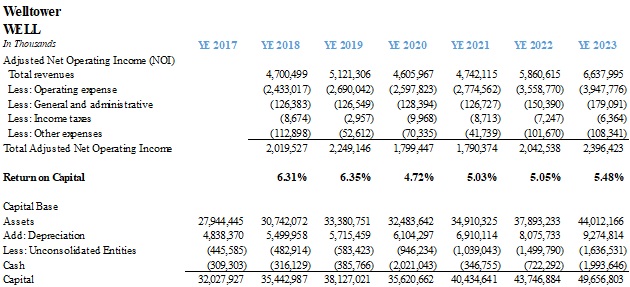

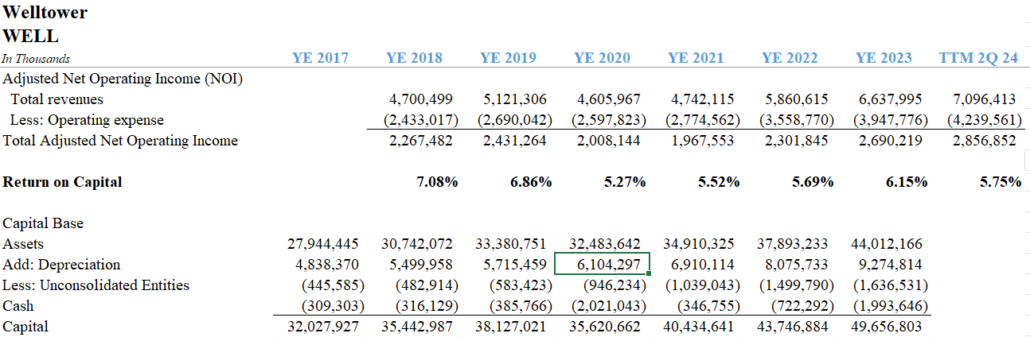

Hindenburg’s questions aside, I don’t see anything nefarious about Welltower. It is just really expensive. Welltower is a business which earns returns on capital around 6% and returns on equity around 7-8%. This won’t set your nanna’s pulse racing. Through 6 months of 2024 reporting, operating income has only risen 5%. Meanwhile, notes receivable from operators have doubled since 2022. Who’s borrowing from Welltower at 10% interest rates? Probably not the most seaworthy. The firm racked up $36 million of impairments in 2023 and $68 million for the TTM period to June 2024. These aren’t horrible figures, but they show that not everything comes up smelling like roses in the senior living business.

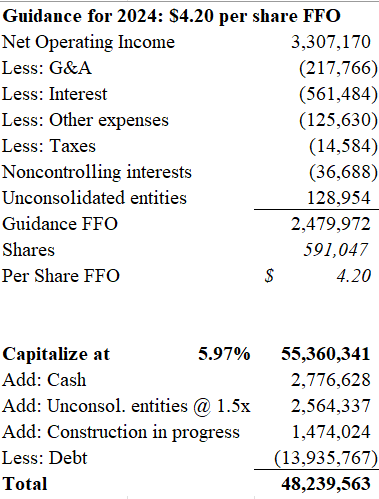

Management recently guided for $4.20 per share in funds from operations (FFO) for 2024. This preferred metric for real estate investment trusts adds back depreciation and other non-cash items. I reverse-engineered the guidance for FFO to arrive at a pro forma net operating income (NOI) for 2024 of $3.3 billion. This NOI calculation takes FFO a step further by removing debt service costs and the administrative costs of running the company to arrive at an unleveraged, asset-level value for the business.

In fairness to Welltower, the increase in NOI is substantial compared with the $2.7 billion generated in 2023. The company has certainly improved operations, pruned underperforming assets, and had much stronger occupancy levels as the post-Covid senior market has recovered. A 22% increase in NOI is impressive for any business, especially a real estate company with slow-moving assets.

How does $3.3 billion of net operating income translate into asset values? I capitalized the income using 5.97% to arrive at a gross asset value of $55 billion.

The 5.97% “cap rate” was derived using the following logic: I simply applied the spread for Welltower’s Standard & Poor’s BBB credit rating to the “risk-free” 10-Year Treasury yield of 4.07% to arrive at a current debt cost of 5.15%. I assumed that the company earns an equity yield just 1% higher than this cost of debt (6.15%) and weighted the equity percentage at 85%. One could argue that this 5.97% cap rate is slightly high. Perhaps I could impute a bigger weighting to the less-expensive cost of debt. After all, Welltower has been able to raise debt at much lower rates in the past.

My counter-argument would be that a lower cap rate would be too aggressive for a business that has a mixture of assets, ongoing charge-offs for underperforming notes receivable, and a collection of diverse and unpredictable operators assigned to the facilities. Finally, I am not making any allowances for capital improvements at existing properties. These assets require nearly $600 million per year in upkeep that is not reflected in NOI. They are, however, certainly an ongoing cash obligation for Welltower. I am being very generous by excluding them in the value computation.

To arrive at a net asset value, I added cash of $2.6 billion as well as construction in progress at book value, and unconsolidated equity interests at 1.5x book value. After subtracting debt of $14 billion, Welltower’s net asset value pencils slightly above $48 billion.

You may say that I’m not appropriately valuing the future. There’s more upside at Welltower, says you. Yes, there is more upside. Unfortunately, as a REIT which is required to distribute its earnings to shareholders, incremental growth can only come from external capital: Sell more stock or raise more debt. When you’re earning returns on capital in the 6% range and you’re borrowing at 5%, you don’t have tremendous opportunities for upside.

I am short Welltower. It’s a $132 stock that should be priced to yield in the mid 3% range around $80-85.

I could leave you with some Jim Morrison lyrics. Instead I will give you something special by Wire. Or you may prefer REM’s 1987 cover version:

“There’s something strange going on tonight.

There’s something going on that’s not quite right

Joey’s nervous and the lights are bright

There’s something going on that’s not quite right.”

Until next time.

Disclaimer:

The information provided in this article is based on the opinions of the author after reviewing publicly available press reports and SEC filings. The author makes no representations or warranties as to accuracy of the content provided. This is not investment advice. You should perform your own due diligence before making any investments.