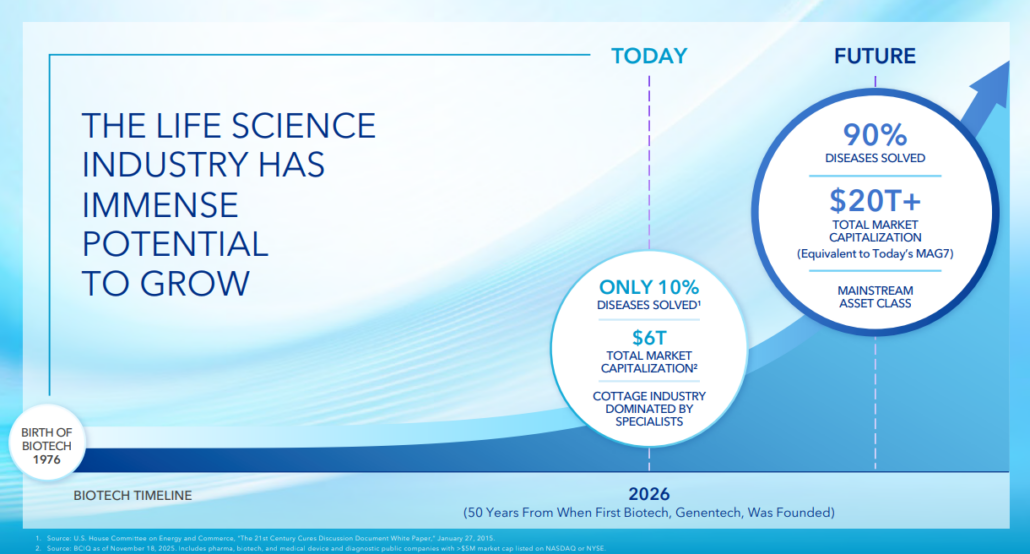

I don’t know if they hand out awards for the most optimistic investor relations team, but the gang at Alexandria Real Estate Equities just opened 2026 with a banger that will surely make them the top candidate. Yes, it’s been a rough three years for the nation’s largest owner of buildings dedicated to the pharmaceutical and biotechnology industries. The share price has fallen by 75% since the pandemic and they just slashed the dividend. But despair not ye of little faith. Just think about all of those diseases out there looking for a cure!

The Alexandria slide deck announces our glorious pharmaceutical future by declaring that only 10% of earthly diseases have been “solved”. That leaves 90% of the rest of the diseases left to cure. Talk about upside! The current market capitalization of the biotechnology industry is estimated by Alexandria to be $6 trillion. Extrapolating this figure for the next 80%, well, that’s another $14 trillion of potential market capitalization lying just beyond the rainbow. The god-like powers of capitalism will save humanity.

Alexandria’s team must have considered the irony of this future. After all, once 100% of the remaining diseases are “solved”, the market capitalization of the biotech industry should be closer to zero than $20 trillion. Realizing the potentially adverse effect of curing all diseases, they left open the possibility that 10% of the remaining diseases are beyond the grasp of even the most miraculous biotechnical engineering.

Because, when you get right down to it, solving all diseases isn’t great for business. No, what we really need is a sort of Munchausen-by-proxy economy. By all means, come up with ways to treat the ills of mankind which improve comfort and extend lifetimes. But cure? Now, hold on there, that’s a lot of jobs we’re talking about. Healthcare is now more than 16% of our nation’s GDP. You know what might work even better? What if we re-introduced diseases that were already “solved”? Take measles, for instance. Who knows? A resurgence of leprosy might be just what we need to avoid the next recession.

Ok, enough joking around. In fairness to Alexandria, much of the presentation describes the precarious state of the life sciences real estate market and the challenges facing the company. The real question before the house is whether shares in Alexandria Real Estate Equities (ARE) offer investors compelling value. The nation’s largest owner of real estate dedicated to scientific research claims that the net value of its assets is far higher than the current $54 share price. Alexandria’s investor presentation asserts that the true value is closer to $94. In my estimation, the shares are worth about $73. However, I won’t be buying stock any time soon. Much of this premium is based upon the book value of an uncertain development pipleine and the value of its speculative securities investment portfolio.

In this article, we’ll take a brief overview of the latest investor presentation, and I will guide you through some numbers that compose my valuation.

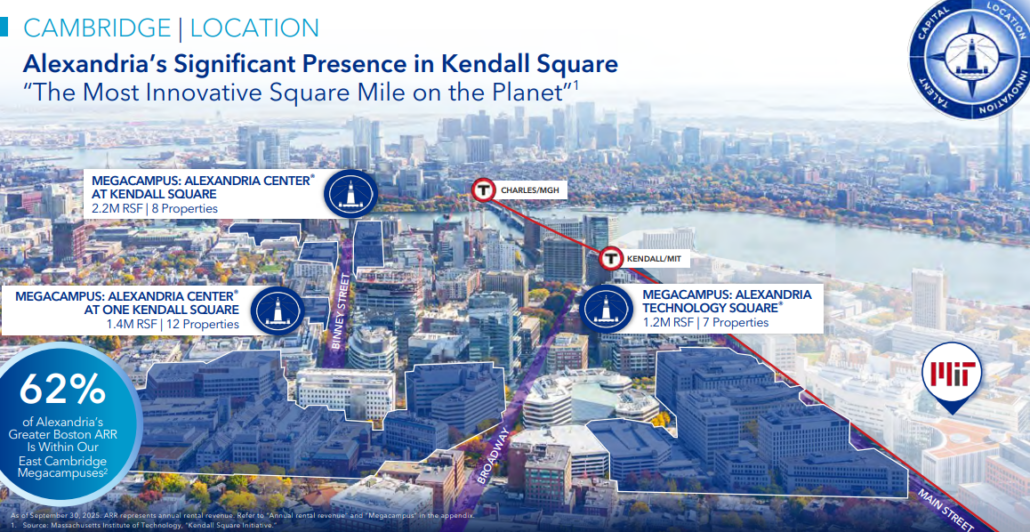

Alexandria has shaped its nationwide real estate portfolio into 26 dynamic innovation campuses. Primary markets include Boston, San Diego, San Francisco, Seattle, and DC. The company boasts a tenant roster of 700 companies in 27.1 million rentable square feet. Tenant retention has been over 80% over the past five years. Scientific innovation thrives when disparate groups of creative thinkers interact on a frequent basis. Despite the rise of remote work, it seems likely that medical technology will continue to emerge from the laboratories and offices of pharmaceutical companies, research universities, and medical device manufacturers.

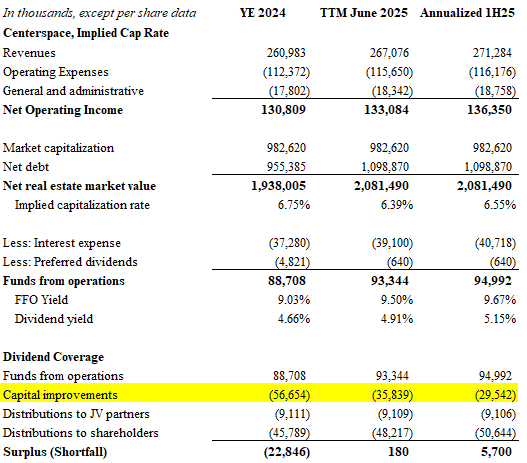

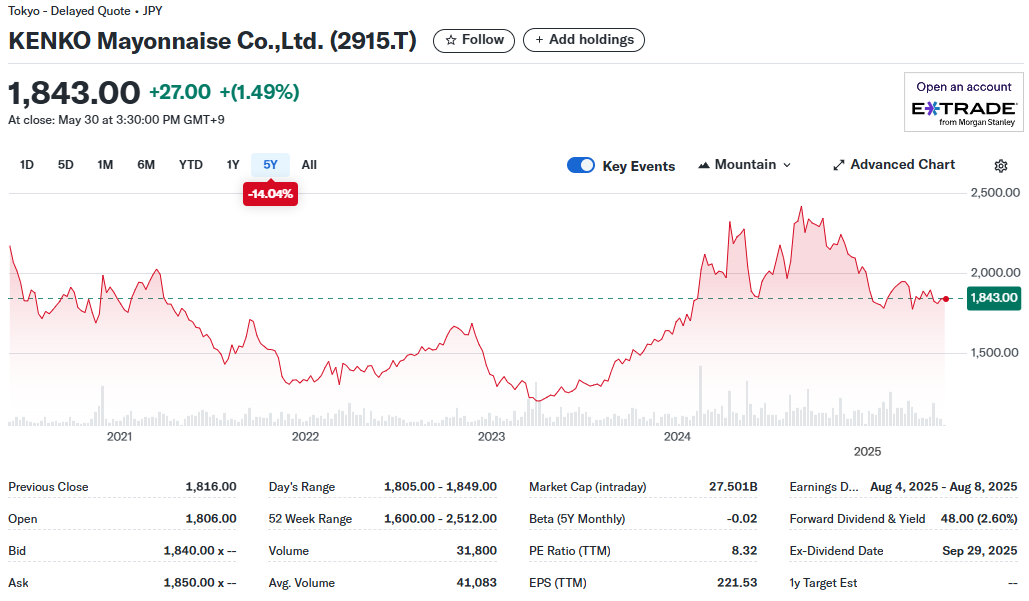

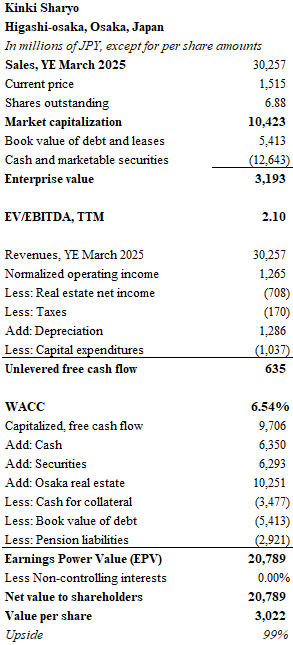

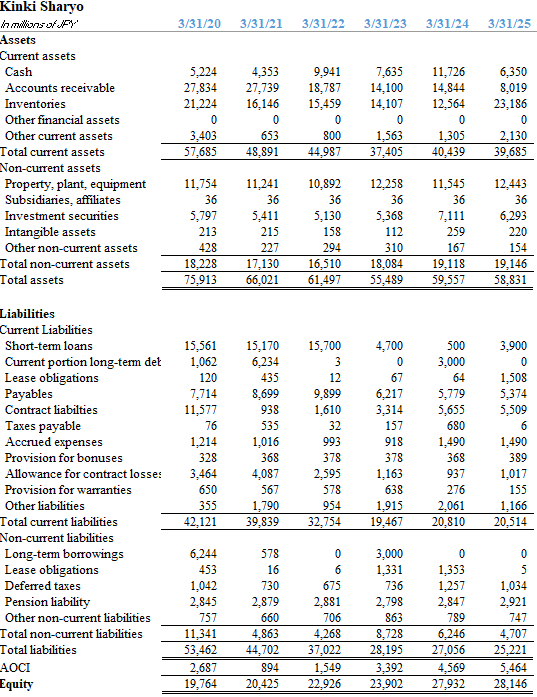

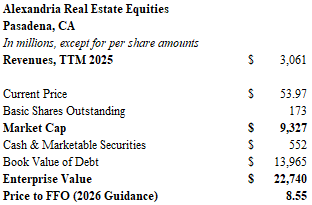

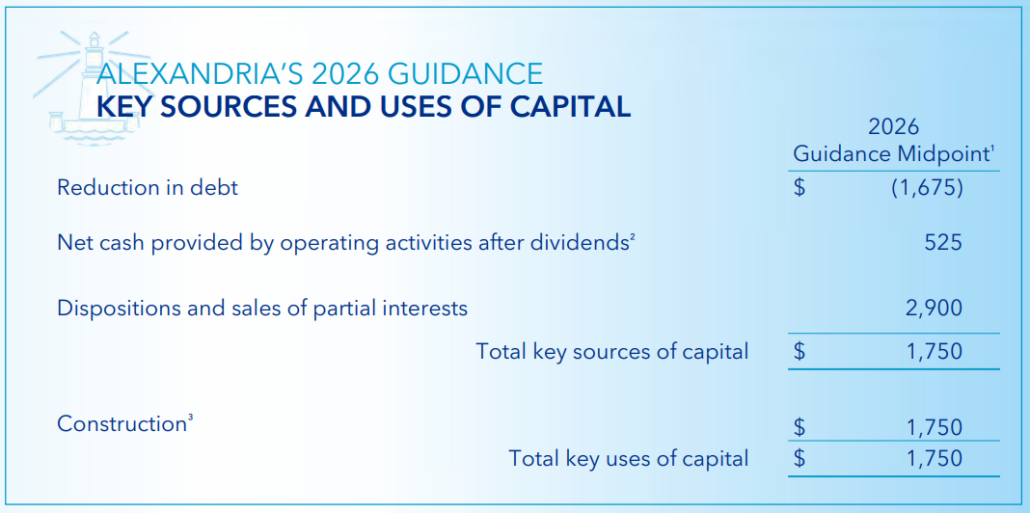

Alexandria trades with a market capitalization of $9.3 billion and the current price allows for a 5.3% dividend yield on the reduced payout. The share price is roughly 8.6 times management’s guide for 2026 funds from operations (FFO). The undepreciated book value of real estate on its ledger amounts to $29.3 billion, with another $8.6 billion of construction in progress at the end of the 3rd quarter of 2025. The company has approximately $13.9 billion of debt and lease obligations. To improve the balance sheet, Alexandria intends to dispose $2.9 billion of “non-core” real estate assets and joint venture interests in 2026. ARE forecasts 2026 operating cash flow (after dividends) of $525 million. The resulting $3.4 billion cash pile will be split: $1.7 billion for debt reduction and $1.7 billion for the completion of construction projects.

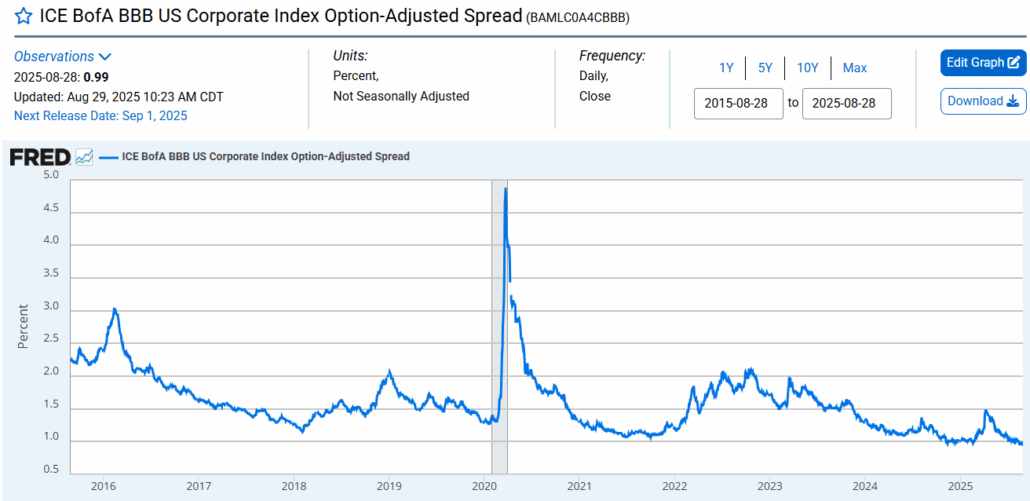

Alexandria is rated BBB+ by Standard and Poor’s but has been placed on a negative credit watch. Still, the company does benefit from a low cost of financing and a long runway for debt maturities. The weighted average interest rate for ARE’s debt is 3.97% and the weighted average maturity is 11.7 years. Unfortunately, recently issued debt came with a 5.6% coupon.

The reasons for worrying about Alexandria’s future are easy to find. Winter has arrived for the medical technology industry. Demand for life science space has fallen 60% since the pandemic. To make matters worse, the most recent Senate budget presents a 40% decline in spending for the National Institutes of Health (NIH) to $48.7 billion. It is estimated that 1,500 jobs will be eliminated. Meanwhile, only about $9 billion of venture capital funding is anticipated for the medical technology industry in 2026. This represents a substantial reduction from 2021 when $41 billion was raised. Pharmaceutical company spending on research and development peaked in 2023 at $317 billion and has fallen the past two years.

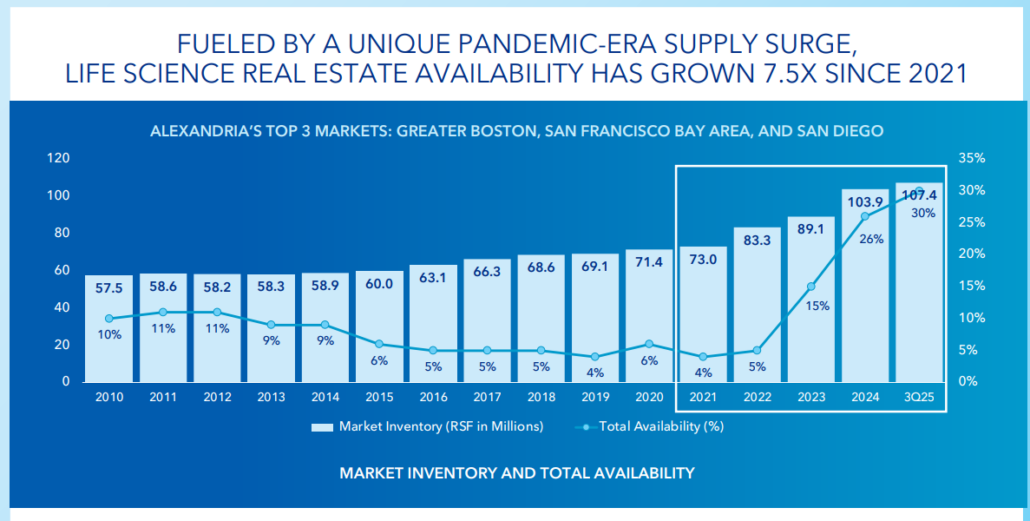

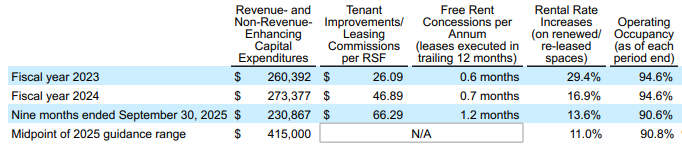

Market occupancy levels have dropped precipitously. Over 30% of space is available in the company’s top three markets of Greater Boston, the San Francisco Bay Area, and San Diego. Occupancy levels at Alexandria’s buildings reflect the industry decline. They fell dramatically from 94.6% at the end of 2024 to 90.6% at the end of the 3rd quarter of 2025. Any time real estate owners see an occupancy level with an 8 in front of it, beads of sweat start to appear. Occupancy at Alexandria is forecast to drop to as low as 87.7% by the end of 2026.

More problems could lie ahead. Alexandria has a plan for 2026, but what about the completion of projects in 2027 and 2028? Future capital raises to finish buildings in progress may be needed, and they will certainly dilute current shareholders. At the end of the 3rd quarter of 2025, Alexandria projected that 4.2 million rentable square feet will be placed into service between the end of 2025 and 2028. 43% of the new space is under lease or in negotiation. This new space is expected to generate more than $390 million of NOI. But that assumes another 2 million square feet has yet to be absorbed in what promises to be a soft market. It could take many years to backfill the overall 30% market availability in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Finally, the entire cost structure of newer assets may face a pricing reset. Capital improvements amounted to $260 million in 2023, but they were expected to rise to $415 million by the end of last year. On a per square foot basis, TI’s and commissions rose from $26 to $66 over three years. Free rent to secure new leases has doubled during the timeframe. Even the strongest pharmaceutical companies will balk at the rental rates on offer and demand substantial concessions.

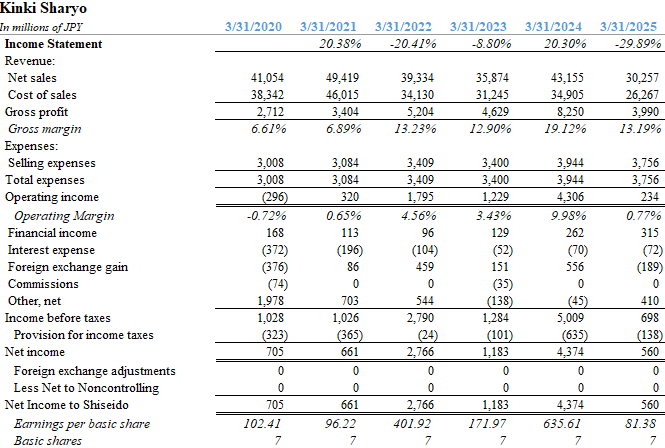

Alexandria forecasts that 2026 FFO will fall from approximately $9 per share in 2025 to $6.40 per share in 2026. While dispositions account for a large portion of the reduction, rents on lease renewals are forecast to fall by as much as 12%. Same-store net operating income will drop by as much as 9% in 2026.

Valuation

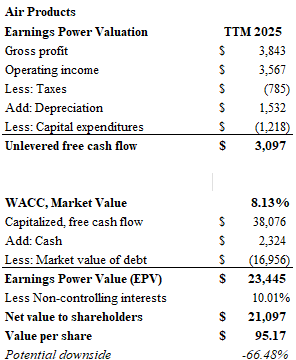

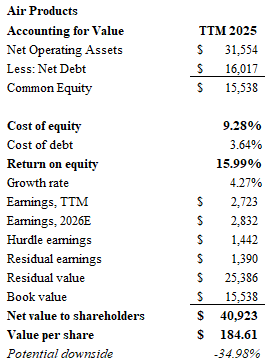

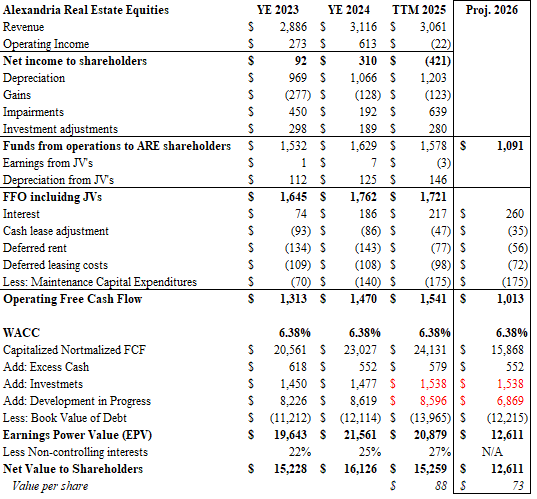

My valuation method is very simple. I took $1.1 billion of projected funds from operations for 2026, added back the forecast interest expense of $260 million, subtracted $175 million for maintenance capital expenditures, and subtracted cash lease adjustments. The cash lease adjustments are identical to the numbers for 2025, but they have been reduced by 27% to estimate the portion attributable to joint ventures. The resulting free cash flow from operations for 2026 is estimated to be approximately $1 billion. This sum was divided by a capitalization rate of 6.38% to arrive at $15.9 billion of value.

Next, I added $552 million of cash on hand, the securities investment portfolio of $1.5 billion and the book value of construction in progress of $6.9 billion. Construction in progress was calculated by subtracting $1.75 billion from the September 2025 balance of $8.6 billion. Finally, after accounting for management’s guidance of $1.75 billion of debt reduction, the 2026 debt level of $12.2 billion was subtracted. The net value is $12.6 billion, or approximately $73 per share.

The table shows the change in computed net asset value over the past three years. In 2023 through 2025, I “grossed up” funds from operations to include joint venture partnerships before capitalizing the cash flow. An adjustment was made at the bottom using a percentage of book value attributable to noncontrolling interests. My calculation for 2025 indicates a net asset value of $88 per share, showing that a substantial decline in the stock was justified.

My capitalization rate is based on a weighted cost of capital where the market value of net debt accounts for 56% of the measure. At a BBB+ rating, the cost of debt was attributed as 5.1%. This is a forgiving number considering the recent placements at higher rates. Equity, the remaining 44% of the weight, was awarded a simple 8% rate. I don’t have a sophisticated explanation for the use of 8%, but it generally “feels right”.

You may think my cap rate is too high considering the gold-plated roster of tenants like Lilly and Merck and the proximity to the best universities in the world. Alexandria touts its asset values utilizing capitalization around 6% and below. Yet, the company has sold assets at cap rates above 8.5%. The building sales may may not represent “core assets,” but such a wide discrepancy can’t persist as long as interest rates remain elevated.

Although the calculation offers the appearance of upside, far too much weight is placed on the book value of construction in progress and the value of the company’s securities. Alexandria often took equity stakes in their tenants in lieu of rent. Given the uncertainty around new drug approvals, much of the securities portfolio could become impaired. Meanwhile the full lease absorption of $6.8 billion of construction in progress is far from certain. In the early years following completion, hefty concessions will be required to attract tenants. One can easily see that a 30% impairment of the development pipeline would eliminate the premium calculated in my valuation. The market may well be ascribing such a discount already.

Alexandria Real Estate Equities offers an intriguing way to invest in the future of the pharmaceutical industry. Medical innovations will continue to emerge, of course, and they may occur more frequently than not at one of Alexandria’s campuses. The company has a best-in-class real estate portfolio and has proven to be a skilled operator and attractor of premier tenants. But nobody is immune to the laws of supply and demand. There is simply too much laboratory space on the market, and the engines of demand are looking fairly dormant. When the government is no longer a key partner in the development of new drugs, your runway looks a lot cloudier. Is there upside? Probably so. But, I think there are better places to put your money in the meantime.

If you are attracted to Alexandria’s robust dividend yield, I would look elsewhere. Some of the pipeline master limited partnerships (MLPs) are more appealing. Western Midstream (WES) and Hess Midstream (HESM) yield about 9%, and the demand for natural gas seems much more reliable as power generation capacity continues to grow. Along those same lines, some of the big miners stand to benefit from the copper and minerals boom. BHP yields 3.5%, Rio Tinto is on 4.6%, and the much riskier Vale yields more than 8%. I would add that the large mining companies provide the added benefit of diversifying away from a deflating dollar.

We’ll leave it there for now. Until next time.

DISCLAIMER

The information provided in this article is based on the opinions of the author after reviewing publicly available press reports and SEC filings. The author makes no representations or warranties as to accuracy of the content provided. This is not investment advice. You should perform your own due diligence before making any investments.